The Lost Art of Snake Illustration

Before cameras, how did scientists capture the dazzling shimmer of a snake’s scales or the intricate patterns of a lizard’s skin? Through the painstaking art of hand-drawn illustrations—each stroke a testament to both scientific curiosity and artistic mastery. In the 19th century, naturalists weren’t just scientists; they were also artists, blending observation with creativity to document the natural world in ink, watercolor, and lithographic prints.

Among these skilled illustrators, two names stand out: John Edwards Holbrook and Leopold Fitzinger. Their works, North American Herpetology and Bilder-Atlas zur wissenschaftlich-populären Naturgeschichte der Wirbelthiere (try saying that five times fast!), set new standards for zoological illustration—combining scientific precision with artistic brilliance. Even today, their illustrations remain admired for their accuracy, beauty, and lasting impact on the study of reptiles and amphibians.

John Edwards Holbrook: The Father of American Herpetology

Born in 1794 in South Carolina, John Edwards Holbrook was initially a medical doctor, but his true passion lay in reptiles. Obsessed with the slithering and scaly creatures of North America, he spent years observing, sketching, and documenting them, culminating in his groundbreaking five-volume work, North American Herpetology (1836-1840). Holbrook wasn’t just theorizing from a dusty office—he ventured into swamps, forests, and riverbanks to study these creatures up close, making his research remarkably detailed for the time.

What truly set Holbrook’s work apart was its stunning illustrations. Partnering with artist J. Sera, he produced hand-colored lithographs so lifelike that they remain valuable references even today. Before photography, these images were crucial for identifying species, and Holbrook ensured they were both beautiful and scientifically precise. His book became the foundation for reptile study in the U.S., introducing new species and compiling the first comprehensive record of North American reptiles.

Snakes in the Spotlight: Holbrook’s Most Captivating Subjects

Holbrook’s illustrations weren’t just scientifically useful—they told the stories of the snakes themselves. Here are three of his most striking subjects:

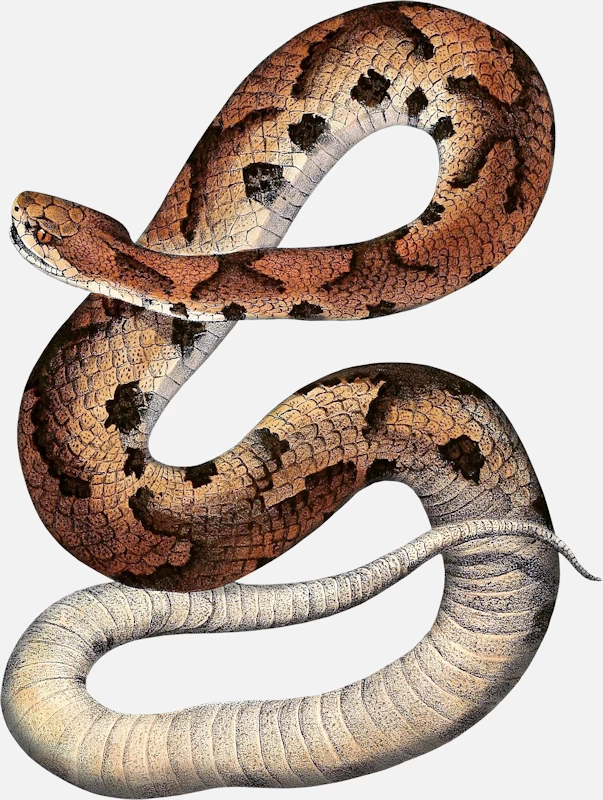

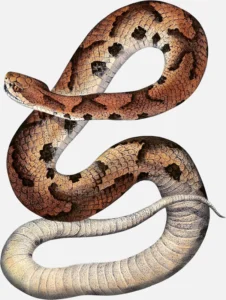

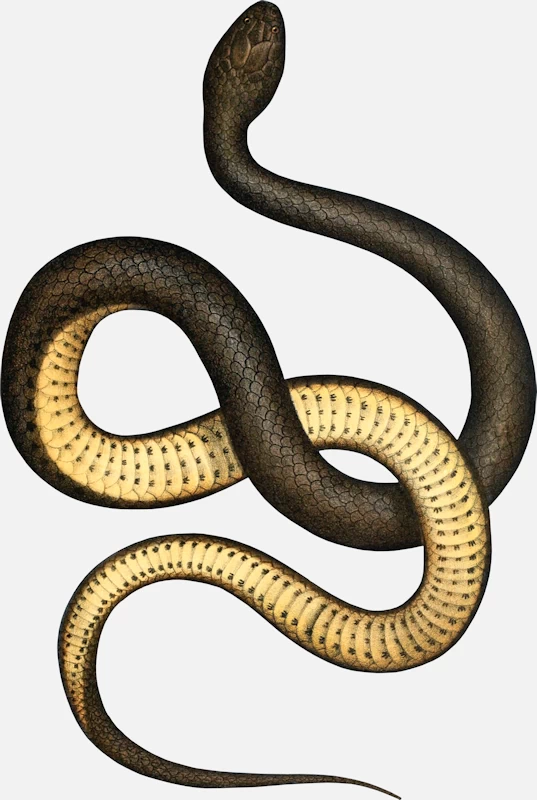

The Eastern Rat Snake: Nature’s Rodent Control

One of Holbrook’s most famous illustrations features the eastern rat snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis), a sleek black serpent often found slithering through barns and trees. Growing up to six feet long, this snake is harmless to humans but a nightmare for rodents. Holbrook’s drawing captures its sinuous form with such precision that you can almost feel it coiling through the grass.

Fun fact: Eastern rat snakes are incredible climbers. Holbrook noted their ability to scale trees in search of bird eggs—an unkind habit if you’re a bird, but an effective survival strategy for the snake!

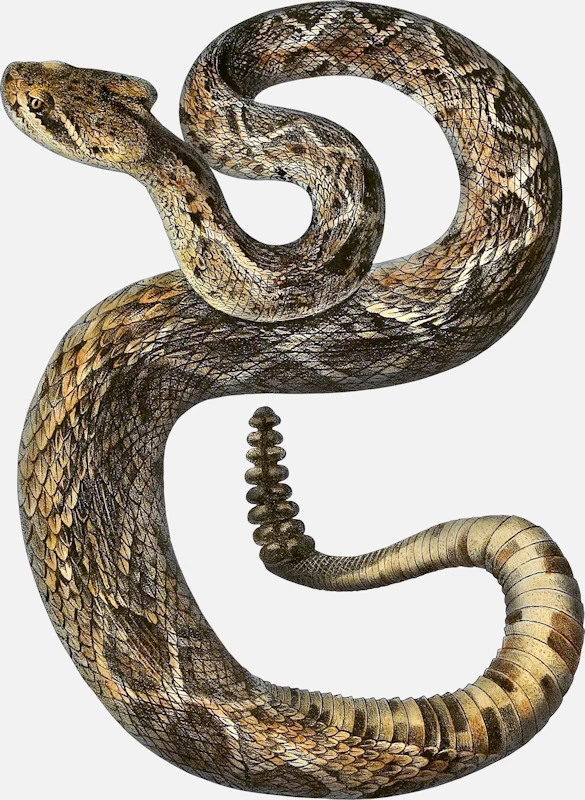

The Coachwhip: A Speed Demon of the Snake World

Next up is the coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum), a long, slender snake named for its whip-like appearance. Holbrook’s illustration captures its streamlined form, emphasizing its agility and lightning-fast movements.

A legend once claimed that coachwhips could chase down humans and lash them like a whip! Of course, this is pure fiction—these snakes would rather escape than attack. Still, their quick movements and alert nature make them notoriously difficult to catch, as Holbrook himself noted in his field observations.

The Rainbow Snake: A Creature of Myth and Mystery

The rainbow snake (Farancia erytrogramma) looks almost magical with its glossy black body accented by vibrant red and yellow stripes. Holbrook’s illustration is so vivid it almost appears to shimmer on the page.

This secretive, eel-eating snake is rarely seen, leading some early settlers to believe it was a mythical creature. Thanks to Holbrook’s meticulous documentation, the rainbow snake became scientifically recognized rather than just a rumor whispered in swampy backwaters.

Leopold Fitzinger: A Global Vision for Reptile Study

While Holbrook focused on North America, Austrian zoologist Leopold Fitzinger (born in 1802) took a more global approach. He wasn’t just a researcher—he was an artist, illustrating his own works and ensuring that every image was both detailed and accurate. His Bilder-Atlas zur wissenschaftlich-populären Naturgeschichte der Wirbelthiere (1867) compiled reptiles from across continents, expanding the world’s understanding of herpetology.

Fitzinger’s talent lay in both classification and illustration. He developed innovative ways to group reptiles based on physical traits, influencing scientific taxonomy for generations. His detailed illustrations allowed naturalists around the world to compare species and study their evolutionary relationships.

Fitzinger’s Most Striking Illustrations

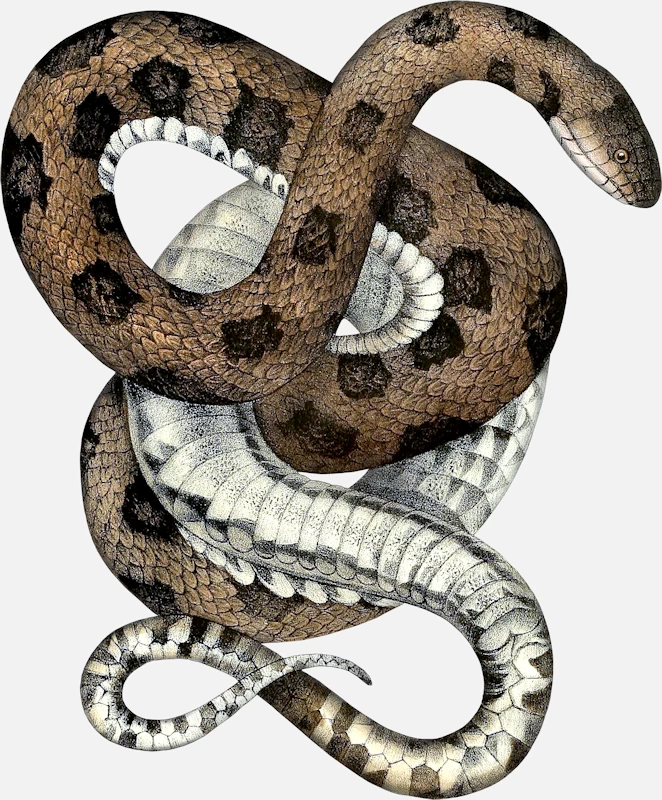

The Aesculapian Snake: A Symbol of Healing and Mythology

One of Fitzinger’s most elegant illustrations is of the Aesculapian snake (Zamenis longissimus), a non-venomous species with a long, slender body and smooth, golden-brown scales. Named after Aesculapius, the Greek god of medicine, this snake has been associated with healing and wisdom for centuries.

Found across Europe, the Aesculapian snake is an exceptional climber, often found in trees and ruins. Fitzinger’s careful rendering captures its graceful form, emphasizing its historical and cultural significance as well as its biological features.

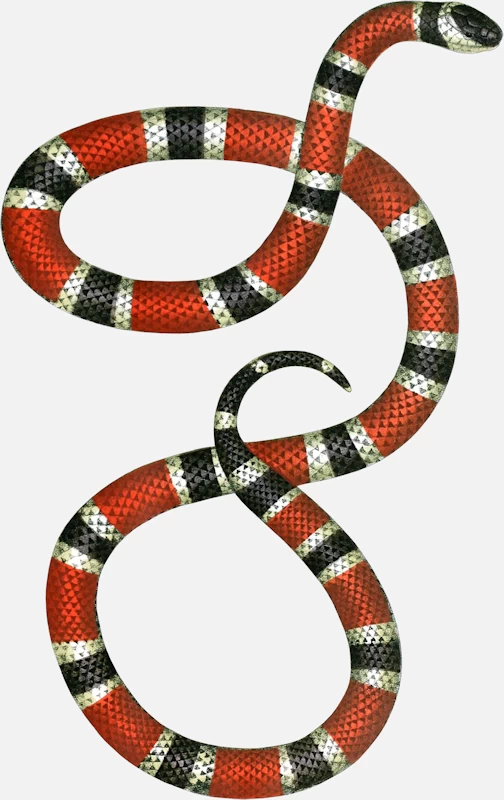

The Painted Coral Snake: A Walking Warning Sign

Few snakes are as eye-catching as the painted coral snake (Micrurus), and Fitzinger’s illustration does it justice. Its bright red, yellow, and black stripes serve as nature’s version of a “Do Not Touch” sign.

With venom potent enough to shut down the nervous system, this snake doesn’t need to be aggressive—predators take one look at its vibrant colors and wisely move along. Fitzinger’s depiction of the snake’s striking patterns remains one of the most detailed ever created.

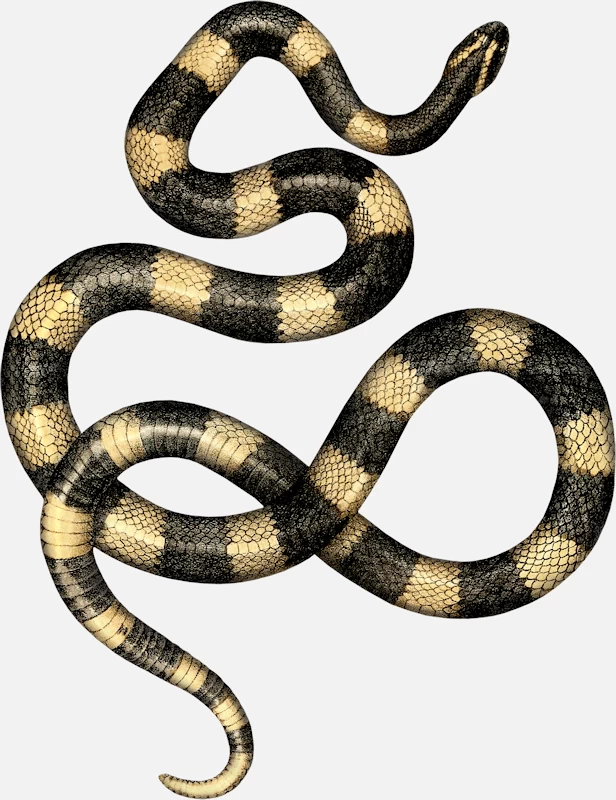

The Banded Krait: Deadly Yet Dignified

Another showstopper from Fitzinger’s collection is the banded krait (Bungarus fasciatus), a highly venomous snake from Southeast Asia. With alternating black and yellow bands, it resembles the coral snake but moves with a slower, more deliberate grace. Fitzinger’s illustration emphasizes its elegant form, making it clear that this is a creature of both beauty and danger.

The Artistic Science Behind the Illustrations

Creating these illustrations was no simple task. Holbrook and Fitzinger relied on detailed field notes, often sketching reptiles in real-time before refining their drawings in the studio. Lithographic prints were then made—an intricate process involving engraving the image onto a stone or metal plate, inking it, and pressing it onto paper. These prints were then hand-colored, often by skilled artists working painstakingly to match the real hues of the animals.

The level of precision required was astounding. Imagine trying to capture the subtle iridescence of a rainbow snake’s scales or the minute texture differences between a lizard’s rough back and its smooth belly—all without the benefit of modern technology. Their work wasn’t just scientific documentation; it was an art form.

Legacy: The Lasting Impact of Holbrook and Fitzinger

Holbrook’s North American Herpetology became the gold standard for reptile studies in the U.S., and Fitzinger’s Bilder-Atlas expanded the world’s knowledge of reptile diversity. Their detailed illustrations continue to be referenced in research papers, museums, and even conservation efforts today.

Even in an age of digital photography and AI-generated images, there’s something irreplaceable about the precision and artistry of hand-drawn illustrations. Holbrook and Fitzinger didn’t just document reptiles—they captured their essence, ensuring these creatures live on in both science and art.

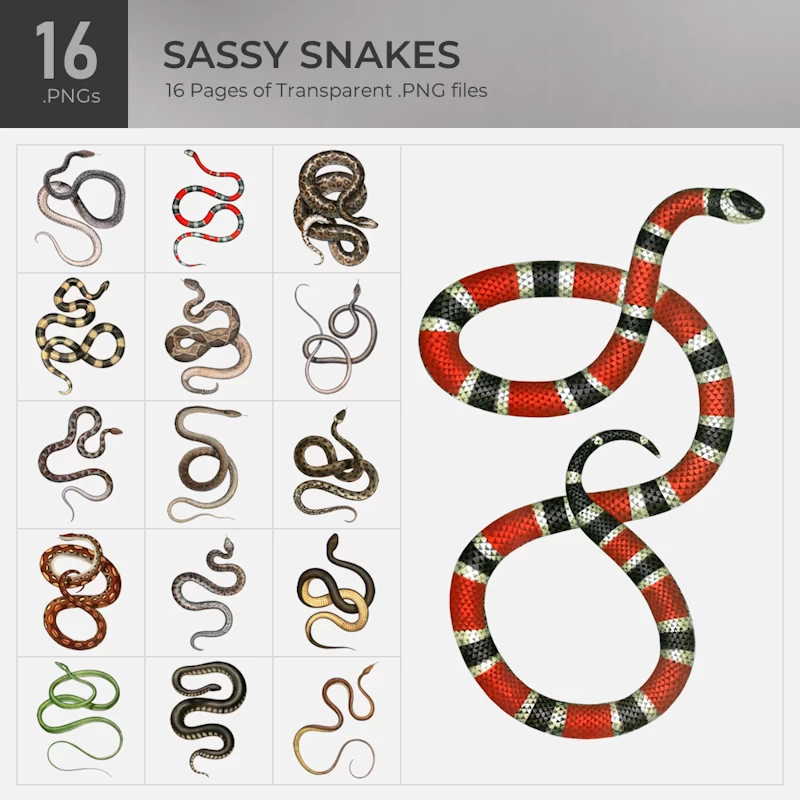

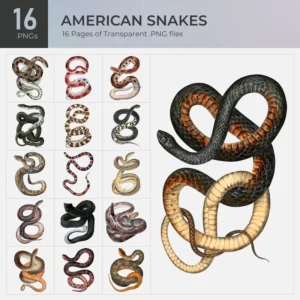

TofuJoe has restored dozens of Holbrook’s and Fitzinger’s snakes and bundled them into two collections. American Snakes features 16 bold drawings from North American Herpetology, and Sassy Snakes boasts images from Bilder-Atlas. They’re SsssUPER! 🐍