When Barnacle Geese Grew on Trees

The barnacle goose myth is one of the weirdest yet oddly charming misconceptions in the history of natural science. Imagine living in a time when people genuinely thought geese grew out of barnacles attached to driftwood. This idea took hold in an era when knowledge of bird migration and reproduction was limited, and people filled the gaps in their understanding with creative—if wildly inaccurate—explanations.

The myth speaks to the broader challenges of medieval science, where observation often blended with imagination. Without tools like microscopes or telescopes, natural phenomena were interpreted through folklore and guesswork. It’s no surprise that the barnacle goose myth isn’t the only head-scratcher from this time—there were also beliefs about animals turning into plants and spontaneous generation (like flies magically appearing from rotting meat). In a world where mysteries vastly outnumbered answers, this myth was just one of many strange attempts to make sense of nature.

Origins of the Myth

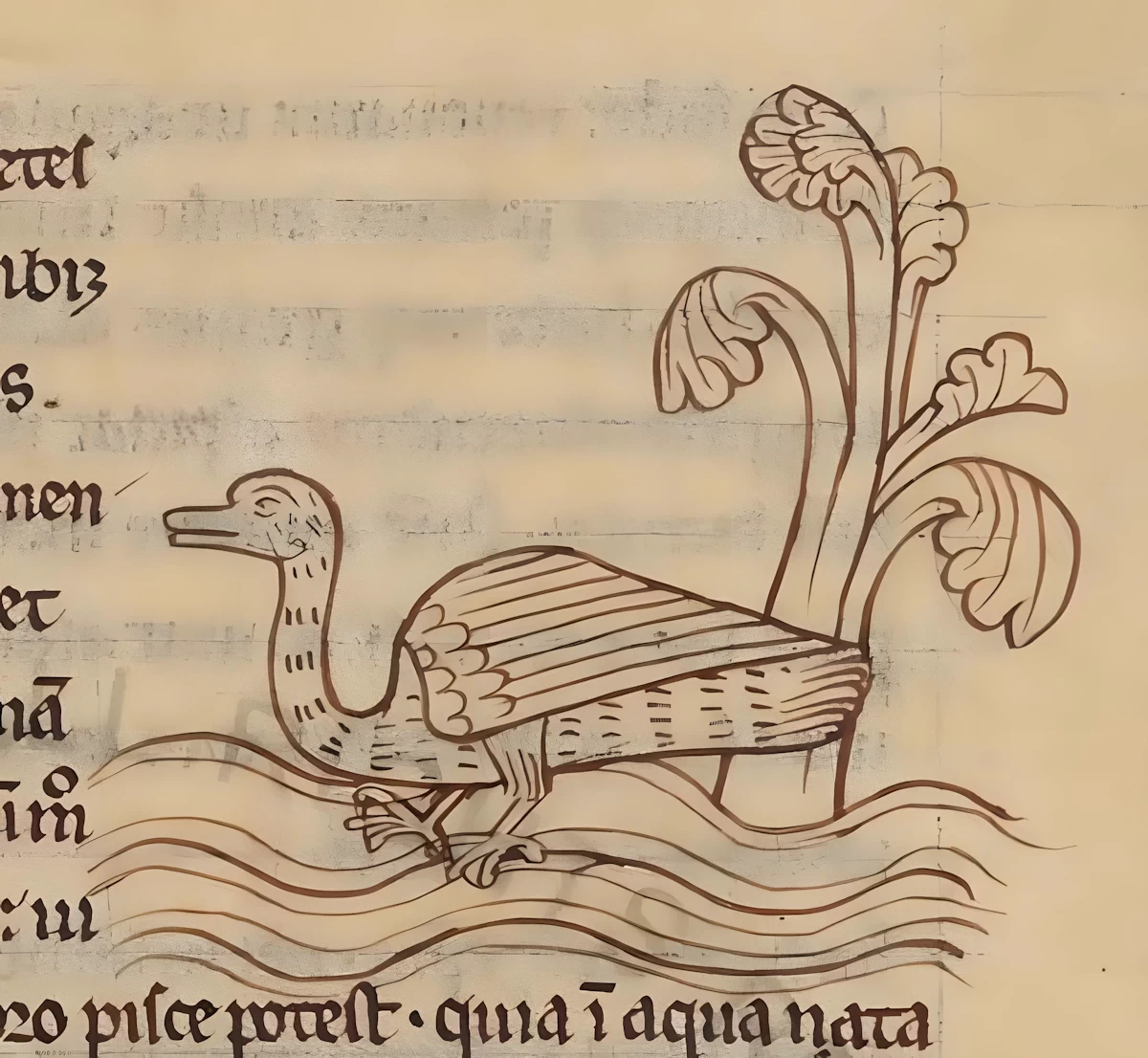

How did people come up with the idea that geese grew out of barnacles? It all started with the mysterious habits of barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis). These migratory birds breed in the Arctic and then head south to Western Europe for the winter. But in medieval times, no one knew where they disappeared to during the summer—after all, few were venturing into the frozen north to find out. Their sudden reappearance each year, with no nests or eggs in sight, left people grasping for explanations.

Meanwhile, goose barnacles (Lepas anatifera) were a common sight along coastlines. Clinging to driftwood, these barnacles had long, flexible stalks and shells that vaguely resembled a goose’s head and neck. It’s not hard to imagine someone looking at these strange sea creatures and thinking, Maybe this is where geese come from! With no visible evidence of barnacle goose eggs, the theory seemed to make perfect sense—after all, if no one had ever seen them hatch, perhaps they simply didn’t.

In a way, this myth was an early attempt at scientific reasoning—just without the right information. Medieval people were skilled at spotting patterns and drawing connections, but sometimes those connections led to wildly inaccurate conclusions.

Medieval Accounts and Beliefs

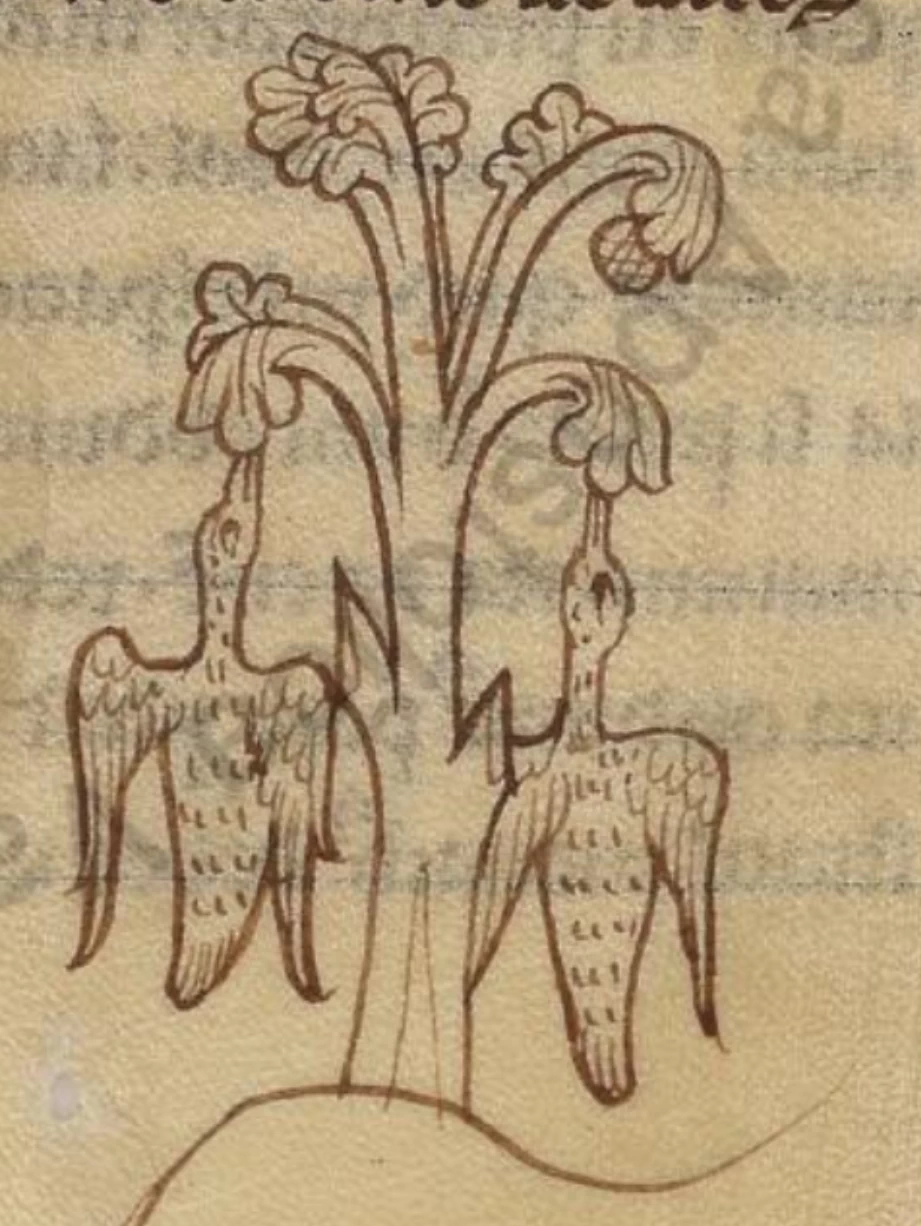

One of the most well-known accounts of this strange goose-barnacle theory comes from Giraldus Cambrensis, also known as Gerald of Wales. In 1187, he documented the belief in his book Topographia Hibernica, describing how people thought barnacle geese spontaneously grew from pieces of driftwood floating in the sea. According to his vivid account, baby geese dangled from the wood by their beaks, slowly transforming from barnacles into fully feathered birds before eventually taking flight.

Gerald wasn’t alone in spreading this tale. The myth persisted for centuries, appearing in natural history books and manuscripts across Europe. What’s particularly fascinating is that these accounts weren’t just the ramblings of superstitious villagers—they were written by scholars, monks, and other educated individuals of the time. Lacking the scientific tools and knowledge, even the brightest minds had to rely on observation, logic, and a bit of imagination. It’s a reminder of how, without proper evidence, even well-intentioned reasoning can lead to some pretty bizarre conclusions.

Implications for Dietary Laws

Here’s where the barnacle goose myth gets even more interesting. The Church had strict rules against eating meat during Lent and on certain holy days, but fish was allowed. Since barnacle geese were believed to originate from the sea, they were classified as fish—not birds—giving people a convenient excuse to enjoy roast goose even when meat was off-limits.

Clergy members were especially fond of this loophole, and some even encouraged the belief to justify indulging in geese during fasting periods. Gerald of Wales, with his usual wit, noted the irony of bending the rules when it suited them. But not everyone was amused—by 1215, Pope Innocent III put an end to the debate, officially declaring barnacle geese as birds. With that, the goose-fish loophole was closed, much to the disappointment of those who had been enjoying their Lenten feasts.

Iconography and Illustrations

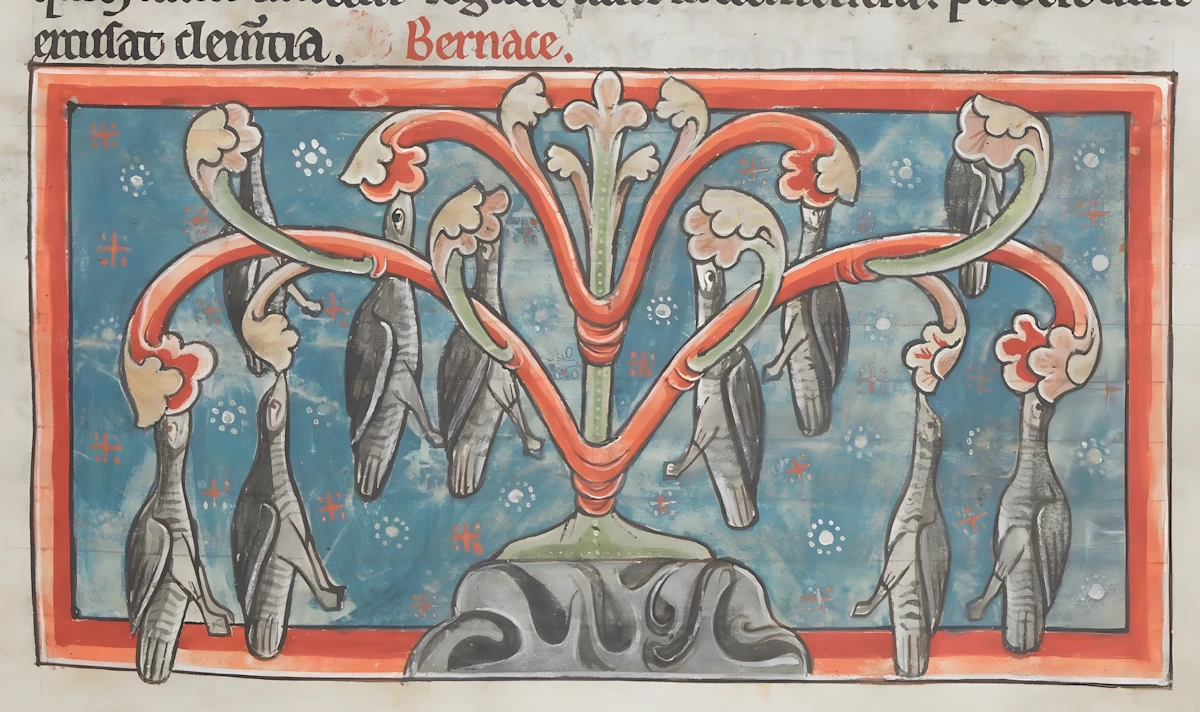

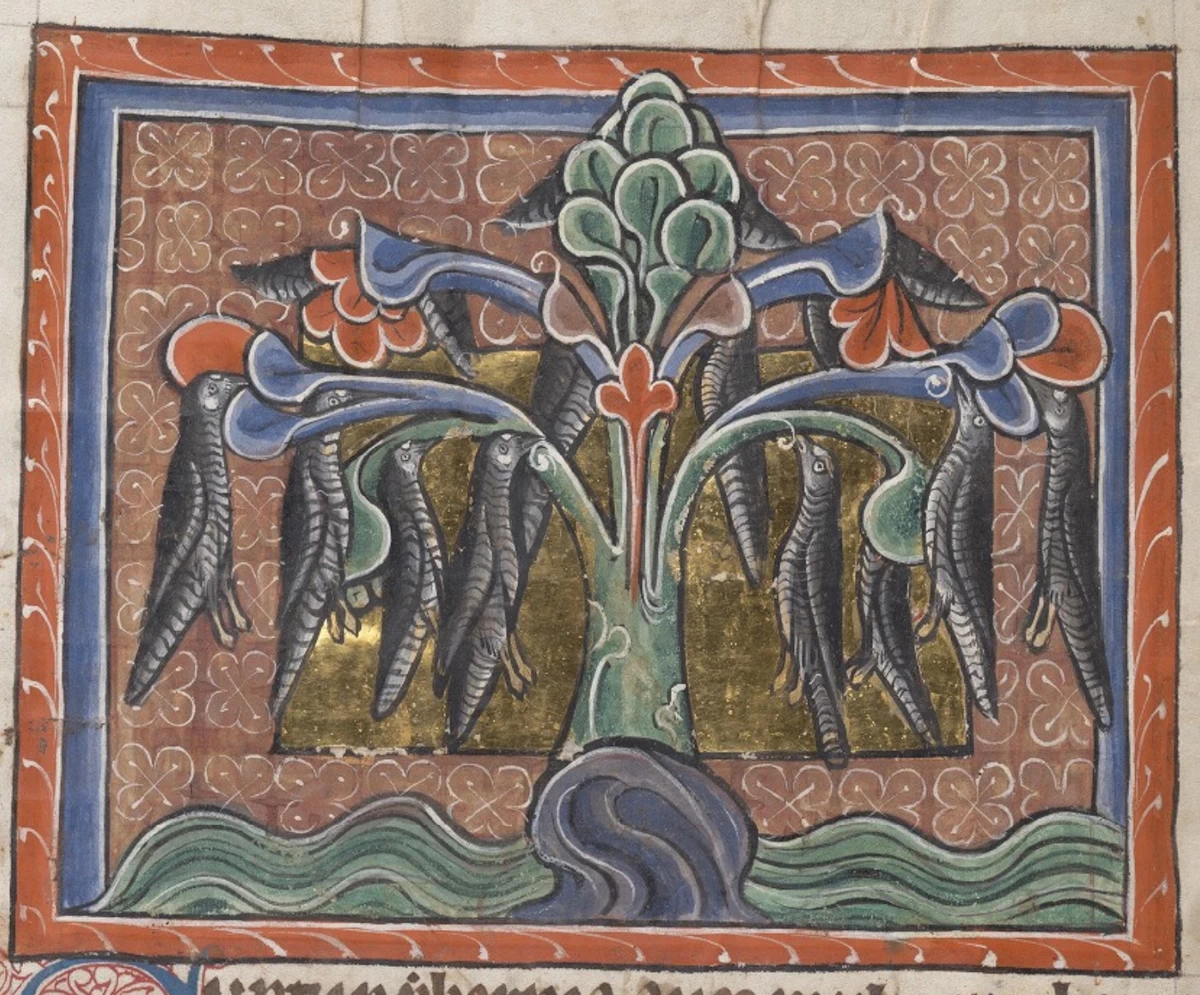

The barnacle goose myth wasn’t just passed down in writing—it was vividly brought to life through art. Medieval manuscripts and natural history books are filled with illustrations of geese emerging from driftwood, making the myth feel all the more believable. After all, seeing is believing, right?

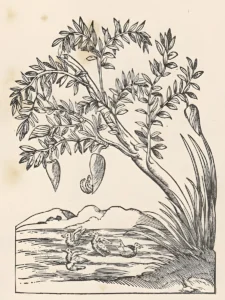

One of the most famous examples comes from Ornithologiae (1603) by Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi, which featured detailed images of geese sprouting from barnacles. Similarly, John Gerard’s The Herball (1597), a widely read botanical book, helped spread the myth with its own imaginative drawings.

These illustrations weren’t just decorative—they were considered scientific documentation at the time. While we now know better, they offer a fascinating glimpse into a world where art and science were deeply intertwined.

Debunking the Myth

As time went on, the barnacle goose myth began to fall apart. By the 17th century, naturalists like Pierre Belon and Francis Willughby started challenging the strange claims. Willughby’s Ornithologiae (1676) provided a more accurate account of the bird’s life cycle, based on observations of its Arctic breeding grounds. With advancing scientific knowledge, it became clear that geese, like all birds, hatch from eggs—no barnacles involved.

The myth’s final demise came with the rise of modern ornithology in the 18th and 19th centuries. As scientists mapped bird migration patterns and studied breeding habits, the idea of geese growing on trees or sprouting from driftwood became as laughable as it sounds today. Still, the tale lingered in popular culture as one of history’s quirkiest misconceptions.

In many ways, debunking the barnacle goose myth reflected a broader shift during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, when people moved away from folklore and toward evidence-based science. Today, historians and naturalists study the barnacle goose myth not just for a laugh, but to understand how medieval people thought about the world around them. It offers a glimpse into the limitations of medieval science, but also into the creativity and ingenuity of people trying to explain the unexplainable. The myth is a great example of how humans will always try to connect the dots, even when the dots are in completely different places!

2 Comments

Comments are closed.