Athanasius Kircher's Kircherian Museum: A Window into 17th-Century Curiosity

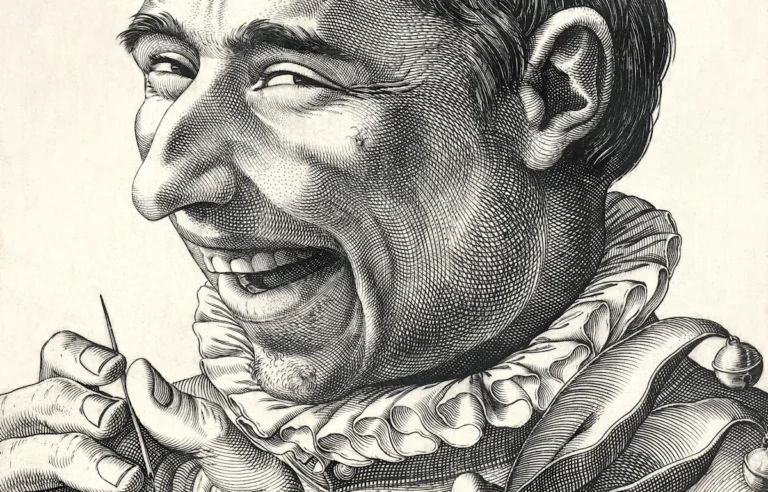

Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit scholar of the 17th century, was a man of boundless curiosity and remarkable intellect. Born in 1602 in Geisa, near Fulda in Germany, Kircher became one of the most celebrated polymaths of his time, delving into diverse fields such as Egyptology, geology, medicine, and music. His intellectual endeavors culminated in the establishment of the Kircherian Museum in Rome, a repository of curiosities that reflected his insatiable quest for knowledge. This museum not only showcased the breadth of Kircher’s interests but also served as a microcosm of the 17th-century scientific and cultural milieu.

The Birth of the Kircherian Museum

Kircher arrived in Rome in 1633, where he eventually became a professor of mathematics at the Collegio Romano, the foremost Jesuit educational institution. The idea for the Kircherian Museum likely germinated during this period. The Collegio Romano already had a collection of scientific instruments and natural specimens, but Kircher’s vision expanded it into a comprehensive cabinet of curiosities, formally established around 1651.

The museum was housed in the Collegio Romano and was initially intended to serve educational purposes. Kircher used the collection to illustrate his lectures and to provide tangible examples of the phenomena he studied. Over time, the museum grew into a public attraction, drawing scholars, dignitaries, and the curious from all over Europe.

The Collections

Natural History

One of the primary focuses of the Kircherian Museum was natural history. Kircher amassed an impressive array of minerals, fossils, plants, and animal specimens. His interest in geology and paleontology was evident in his collection of fossils, which included what he believed were the remains of mythical creatures such as dragons and griffins. These interpretations, while fantastical, were reflective of the era’s attempts to reconcile observable phenomena with ancient texts and myths.

Kircher’s herbarium was another highlight, featuring plants from various parts of the world, some of which were new to European botanists. He meticulously documented these specimens, contributing to the burgeoning field of botany. Each specimen was labeled with detailed notes on its origin, appearance, and uses, providing valuable information for scholars and physicians.

Archaeology and Ethnography

Kircher’s fascination with ancient cultures was a significant aspect of the museum. He is often regarded as one of the pioneers of Egyptology, and his collection included numerous Egyptian artifacts, including mummies, statues, and hieroglyphic inscriptions. Kircher’s attempts to decipher hieroglyphs, though largely incorrect, laid the groundwork for future scholars. His belief that hieroglyphs were a form of symbolic language rather than literal representation influenced later work in the field.

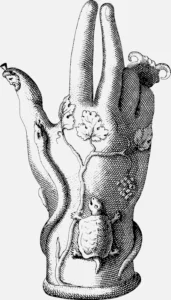

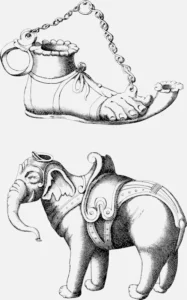

In addition to Egyptian artifacts, the museum housed objects from other ancient civilizations, such as Greek and Roman coins, Etruscan vases, and Assyrian relics. Kircher also collected items from non-European cultures, including Chinese, Indian, and Native American artifacts, reflecting the Jesuit missions’ global reach. These objects provided insight into the customs, technologies, and artistic achievements of diverse cultures, fostering a broader understanding of the world’s heritage.

Scientific Instruments

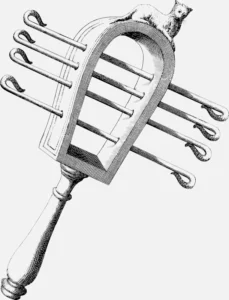

As a mathematician and physicist, Kircher placed great importance on scientific instruments. The museum featured a wide range of devices, from telescopes and microscopes to clocks and automata. One of the most intriguing exhibits was Kircher’s magnetic clock, a complex mechanism that demonstrated the principles of magnetism. This clock was not just a timekeeping device but also a teaching tool that illustrated the invisible forces at work in nature.

Kircher’s interest in acoustics and music was also well represented. The museum housed a variety of musical instruments, including exotic ones like the Chinese gong and the Indian sitar. Kircher even constructed an aeolian harp, an instrument played by the wind, which fascinated visitors with its eerie, ethereal sounds. His studies in acoustics led to the invention of new instruments and improvements in the design of existing ones, contributing to the field of musicology.

Curiosities and Oddities

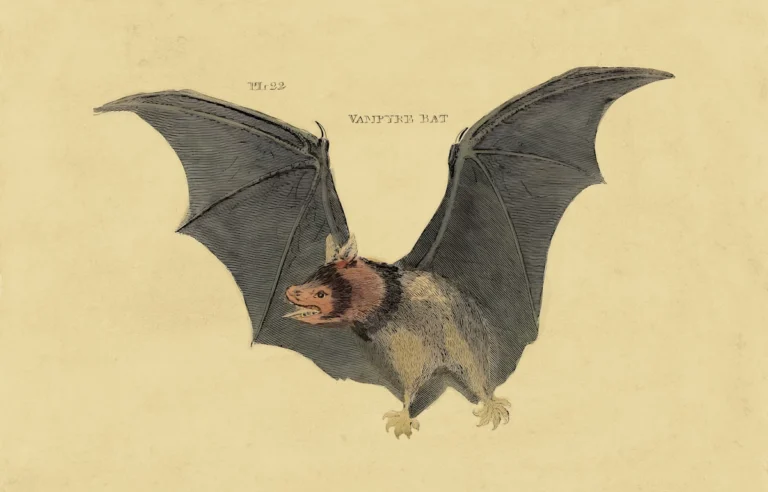

No cabinet of curiosities would be complete without its share of oddities, and the Kircherian Museum was no exception. Among the more peculiar exhibits were a stuffed hippopotamus, a mermaid (likely a taxidermic composite of a monkey and a fish), and a unicorn horn (which was probably a narwhal tusk). These items captured the imaginations of visitors and exemplified the era’s blend of science and mythology. Kircher’s willingness to include such curiosities in his collection demonstrated his openness to exploring the unknown and the mysterious.

Kircher’s museum also included numerous optical illusions and mechanical devices designed to entertain and educate. One popular exhibit was a camera obscura, an early form of the camera that demonstrated the principles of light and vision. Visitors could observe how images were projected onto a surface through a small hole, providing a practical demonstration of optical principles.

The Impact of the Kircherian Museum

The Kircherian Museum was more than just a collection of objects; it was a manifestation of Athanasius Kircher’s intellectual pursuits and his desire to understand the natural and cultural world. The museum played a crucial role in the dissemination of knowledge during the 17th century, serving as a hub for scholars and the public alike.

Educational Contributions

Kircher used the museum as a teaching tool, integrating the collection into his lectures and writings. His books, such as “Mundus Subterraneus” and “Oedipus Aegyptiacus,” were richly illustrated with engravings of the museum’s objects, making his findings accessible to a wider audience. Kircher’s interdisciplinary approach, blending observation with experimentation, was a precursor to modern scientific methods. He emphasized the importance of empirical evidence and encouraged his students to engage in hands-on learning.

Kircher’s correspondences with other scholars further amplified the educational impact of his museum. He exchanged ideas and specimens with scientists across Europe, contributing to a network of knowledge that transcended national borders. His museum became a focal point for intellectual exchange, fostering collaboration and innovation.

Influence on Later Collections

The Kircherian Museum set a precedent for future museums and collections. Its comprehensive scope and public accessibility inspired similar institutions across Europe. The museum’s model of combining education with entertainment influenced the development of later museums, such as the British Museum and the Louvre. The concept of a museum as a place for public learning and engagement can be traced back to Kircher’s pioneering efforts.

Legacy

Although the original Kircherian Museum no longer exists, its legacy endures. Many of Kircher’s objects were transferred to other collections after his death, and some can still be seen in the Museo Nazionale Romano and the Vatican Museums. Kircher’s eclectic approach to collecting and his efforts to catalog and understand the natural and cultural world remain influential. His work laid the foundation for the interdisciplinary studies that characterize modern research institutions.

Kircher’s contributions to science and culture extended beyond his museum. His publications, correspondence, and inventions had a lasting impact on various fields, from linguistics to engineering. Kircher’s holistic approach to knowledge, integrating science, art, and spirituality, continues to inspire scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Conclusion

Athanasius Kircher’s Kircherian Museum was a remarkable institution that captured the spirit of 17th-century intellectual curiosity. Through his diverse and extensive collection, Kircher sought to explore and explain the mysteries of the natural world, ancient civilizations, and scientific phenomena. The museum not only reflected Kircher’s vast knowledge and interests but also served as a vital educational resource and a precursor to modern museums. Today, the legacy of the Kircherian Museum reminds us of the enduring human quest for knowledge and the importance of preserving and sharing our collective heritage.

Kircher’s vision of a museum as a dynamic space for learning and discovery set the stage for the evolution of museums into institutions of public education and cultural preservation. His work exemplifies the Renaissance ideal of the polymath, whose curiosity knows no bounds and whose contributions transcend disciplinary boundaries. As we reflect on the Kircherian Museum, we are reminded of the value of curiosity, the power of interdisciplinary inquiry, and the timeless pursuit of understanding the world around us.