Moldy Fruit: Public Domain Decay Illustrations

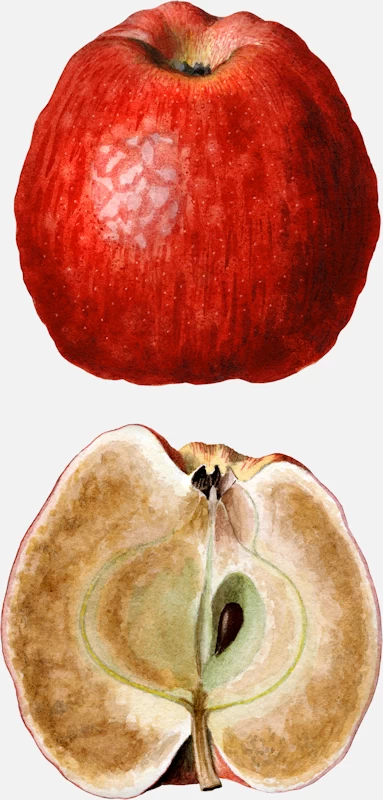

Picture this: a plump peach, its golden skin glistening in the sunlight, ripening to perfection—until, days later, it sags, speckled with mold. Now imagine that transformation captured in breathtaking detail by artists a century ago. Welcome to the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection, where fruit doesn’t just ripen—it tells a story.

The Birth of a Collection: When Art Met Agriculture

Before Google Images, before glossy seed catalogs, if you wanted to show someone what a ‘Rambo’ apple looked like, you had two choices: describe it in agonizing detail (“sort of red, but not too red, a little stripey…”) or paint it. The USDA wisely chose the latter.

In the late 1800s, American agriculture was booming. Farmers were developing new fruit varieties, and the USDA, founded in 1862, needed a way to track them. Enter the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection, an archive of over 7,500 paintings, lithographs, and drawings, created as a visual reference for farmers, scientists, and horticulturists.

The Creative Minds Behind the Collection

The artists behind these watercolors weren’t just skilled—they were pioneers, especially the women, who were working in a field that rarely acknowledged them. Three standouts in particular—Deborah Griscom Passmore, Amanda Almira Newton, and Royal Charles Steadman—brought fruit to life on paper. But let’s not forget James Marion Schull, whose illustrations also captured the intricate beauty of decay, adding to the rich tapestry of this visual archive.

- Deborah Griscom Passmore didn’t just paint fruit—she painted over 1,500 of them, which means she probably spent more time staring at apples than most orchard owners. Her delicate precision made each piece so lifelike you could almost taste it.

- Amanda Almira Newton had an eye for imperfection. While other artists focused on flawless fruit, she embraced the bruises, blemishes, and rot. If fruit had dating profiles, hers would be the unfiltered ones.

- Royal Charles Steadman was the scientific documentarian of the group. Every wrinkle, spot, and imperfection—if your pear had a bad day, he was there to record it.

- James Marion Schull brought his own flair to the collection. Known for his vivid depictions of fruit suffering the ravages of time and disease, his work captured the process of decay with a precision that combined both art and education. His depictions of fruit were not just aesthetic but served as scientific illustrations, showing the effects of rot, pests, and diseases with a unique artistic touch.

The Role of Rotten Fruits

At first glance, painting rotten fruit seems like an odd choice. But these decayed specimens were essential educational tools. In an era before modern agricultural research tools, farmers couldn’t just search “apple rot causes” online. Instead, they relied on collections like these to identify diseases and pests threatening their crops.

For example, black rot—a fungus that starts as small dark spots before spreading into a full-blown disaster—was meticulously illustrated in these paintings. Farmers could compare their own apples to these images and intervene before their entire orchard was ruined. Other paintings captured insect damage, like the dreaded codling moth, whose larvae burrow through apples, leaving behind a mushy, worm-infested mess.

A Closer Look At The Art of Decay

There’s something almost poetic about a painting of a fruit in decline. The deep purple of a Concord grape, now interrupted by withering black patches. A once-plump apple, now sunken, its skin curling inward like an autumn leaf. These paintings don’t just document rot—they turn it into art.

Take James Marion Schull’s 1919 depiction of a decayed pineapple. The spiky crown still stands tall, but the fruit’s once-bright yellow flesh has darkened, its surface marred by patches of mold and softening rot. The contrast between the rigid, structured leaves and the sagging, decomposing body of the pineapple makes for a striking composition—a reminder that even the most resilient fruits succumb to time.

Elsie E. Lower’s 1910 painting of a Lisbon lemon offers another hauntingly beautiful portrayal of decay. The lemon’s dimpled yellow skin, once taut and vibrant, is now horrifyingly green and moldy, its once-firm structure beginning to collapse inward. The delicate brushstrokes capture the fine line between freshness and spoilage, transforming a simple lemon into a study of impermanence.

Schull’s 1912 illustration of Grimes and Spitzenberg apples takes decay to another level, showing not just the effects of rot but the interplay between different apple varieties as they wither. The once-crisp skins have softened and dulled, their colors blending into an autumnal palette of deep reds and browns. Some areas appear almost liquefied, a chilling reminder of how quickly nature reclaims its own.

The Legacy of the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection

So, why does this collection of fruit paintings still matter today? In a world where we can snap high-definition photos of produce with a quick tap on our phones, these century-old watercolors remain relevant. They provide a historical snapshot of fruit varieties—many of which no longer exist—and offer insight into how farmers fought plant diseases long before modern pesticides and research labs.

Beyond agriculture, the collection stands as a testament to the artists who created it. Their work reminds us that beauty can be found even in imperfection—whether it’s a bruised apple or a shriveled pear.

Thanks to digitization, the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection is now accessible to the world. Whether you’re a scientist studying plant diseases, a historian researching agricultural practices, or an art lover admiring delicate brushstrokes, this collection has something to offer.

A Celebration of Life and Decay

At its core, this collection isn’t just about fruit—it’s about life itself. The rise and fall, the ripening and the rotting, the beauty and the breakdown. It reminds us that even the most ordinary things—a peach, an apple, a pear—have a story to tell.

So next time you spot a bruised banana on your counter, don’t just see it as past its prime. See it as part of a centuries-old story—one that artists, scientists, and farmers have been telling since the first apple fell from the tree.