The First English Book on Witchcraft: "The Discoverie of Witchcraft" by Reginald Scot

The Discoverie of Witchcraft is a pretty big deal when it comes to the history of witches, magic, and even stage illusions. Written by Reginald Scot and first published in 1584, it holds the distinction of being the very first comprehensive book on witchcraft. But Scot wasn’t just aiming to spook people with tales of broomsticks and cauldrons—he had a much bigger goal in mind. He was trying to push back against the rampant belief in witches, spells, and all things supernatural. This was a time when you could be accused of being a witch for something as simple as having a weird mole, and Scot wasn’t having it.

At a time when witch trials were tearing through Europe like wildfire, Scot used his book to challenge superstitions head-on. It wasn’t just about debunking witches—The Discoverie of Witchcraft also became the first book to discuss stage magic and illusions. That’s right, before David Copperfield and Harry Houdini, Reginald Scot was explaining how magicians could pull off their “supernatural” tricks. So, in a way, Scot not only contributed to the decline of witch hunts but also to the rise of modern magic shows. Quite the legacy for a man who lived in a time when most people still believed in dragons.

The World During Scot’s Time

The 1500s were brutal for anyone unlucky enough to be accused of witchcraft. Europe was neck-deep in what’s now known as the Witch Hunt period, a time when pointing a finger at someone and calling them a witch was enough to ruin their life—if not end it. Women (and sometimes men) were accused of causing everything from bad weather to crop failures. Did the bread go moldy too fast? Must’ve been a witch. Got a mysterious rash? Definitely witchcraft. Logic was in short supply, and fear was in abundance.

Laws like England’s Witchcraft Act of 1542 gave legal backing to this madness. If someone was suspected of witchcraft, they could be tried and executed. Often, these accusations came from nothing more than rumors or personal grudges. A woman who kept a cat or knew a bit too much about herbs was immediately suspect. The courts? They weren’t looking for proof; they were looking for someone to blame.

And if that wasn’t bad enough, there were “helpful” manuals like The Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), which basically served as a how-to guide for spotting, accusing, and punishing witches. Written in 1487, it taught people how to root out supposed witches based on absurd criteria—like whether they had a birthmark or even if they seemed “too close” to their pets. It was all the rage among witch hunters, but it only added fuel to the fire of fear sweeping across Europe. Innocent people paid the price for the world’s paranoia, and the hysteria only grew stronger.

Enter Reginald Scot

Enter Reginald Scot, born in 1538 in Kent, England. Now, Scot wasn’t some magical rebel fighting witches with a staff and wand—he was a well-educated English gentleman, a scholar, and a member of Parliament. In a time when most people were running scared from witches, Scot was among the few who looked around and said, “Hold on a second, this doesn’t add up.” Unlike his peers, he didn’t buy into the supernatural hype. He wasn’t convinced that these supposed witches were responsible for the misfortunes happening around them. To him, this wasn’t a battle of good versus evil; it was a battle of ignorance versus reason.

Scot believed many of the accused witches were just unfortunate souls who got caught up in people’s fears. Maybe they were old, poor, or simply knew a little too much about herbal medicine. And yes, while there were definitely tricksters out there, Scot argued that the majority of those accused of witchcraft were innocent. They weren’t casting spells; they were just victims of an overactive imagination and a society that was quick to accuse and even quicker to punish.

In 1584, Scot published The Discoverie of Witchcraft, a book that dared to say what no one else would—that witchcraft wasn’t real. At least, not in the magical sense people believed. Scot took on the establishment, challenging both the Church and the government, who had a vested interest in promoting witch trials. It wasn’t just brave; it was revolutionary.

What’s in the Book?

So, what exactly did Scot write that caused such a stir? The Discoverie of Witchcraft is divided into multiple sections, and Scot didn’t pull any punches. One part of the book dives into the myths surrounding witches, systematically debunking them. Scot didn’t just claim that witches lacked supernatural powers—he backed it up with reason. He pointed out how many accusations of witchcraft were based on nothing more than fear and misunderstanding, and he also exposed how the Roman Catholic Church had used these fears to maintain control over the population. In other words, the so-called witches were often scapegoats for larger societal problems.

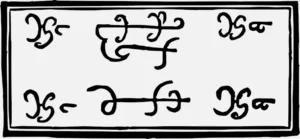

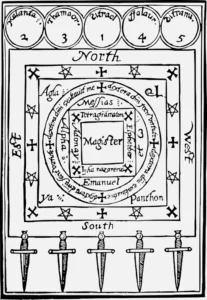

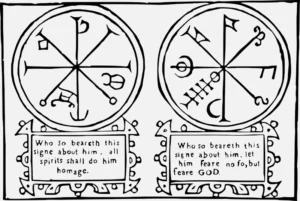

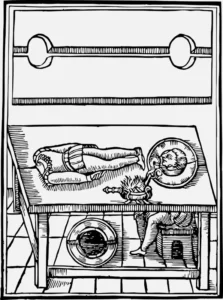

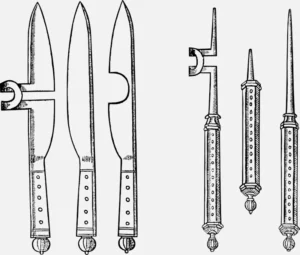

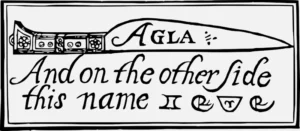

But Scot wasn’t done. He went a step further and discussed how many magical effects or “spells” could be explained as nothing more than sleight of hand or clever trickery. This is where his book gets really interesting. The Discoverie of Witchcraft is the first book to explain the methods behind what we’d now call stage magic. He revealed how magicians could make objects disappear, how they created the illusion of pulling coins out of thin air, and how they used misdirection to trick their audience.

For instance, Scot broke down how performers used hollowed-out cups to “magically” transform objects or how they could use mirrors to create the illusion of invisibility. By doing this, he hoped to show people that what they were witnessing wasn’t magic but skillful deception. His work became a cornerstone for modern magicians, and even today, many illusionists look back at Scot as one of the pioneers of their craft.

But it wasn’t just magic that Scot tackled. He also wrote about astrology, alchemy, and other mystical practices, questioning whether these phenomena had more to do with natural science than with the supernatural. Scot’s approach was groundbreaking because it wasn’t just an attack on witches—it was a plea for rational thought in a world driven by superstition.

The Backlash

As you can imagine, The Discoverie of Witchcraft didn’t go over well with everyone. The Church, for instance, wasn’t too thrilled about someone publicly stating that witches weren’t real. After all, fear of witches helped the Church maintain control over a terrified population. Worse still, Scot’s skepticism directly challenged King James VI of Scotland (who later became King James I of England). King James was a firm believer in witches and even wrote his own book, Daemonologie, in 1597 to defend the necessity of hunting witches.

When James became King of England, he wasn’t about to let some book undermine his authority on witches. He ordered all copies of Scot’s work to be burned. It was an extreme form of censorship, but it didn’t completely erase Scot’s influence. Though many copies were destroyed, a few survived, and the ideas within them couldn’t be erased from history.

A Legacy That Lasts

Despite the backlash, The Discoverie of Witchcraft left a lasting legacy. While it didn’t immediately put an end to witch trials, it planted the seeds of skepticism that grew over time. Scot’s ideas influenced future thinkers who would go on to promote reason, skepticism, and scientific inquiry. His work is considered a precursor to the Enlightenment, a period when people began to question old superstitions and focus more on logic and science.

Perhaps one of the most famous fans of Scot’s work was Harry Houdini. The legendary escape artist and magician owned a first edition of The Discoverie of Witchcraft and considered it one of his most prized possessions. Like Scot, Houdini was determined to expose frauds who claimed supernatural abilities, and Scot’s book served as a major inspiration.

The book’s influence extended beyond just witchcraft and stage magic. It also contributed to the decline of witch hunts, as fewer people were willing to buy into the hysteria after reading Scot’s arguments. Over time, witch hunts faded away, though not before causing significant suffering and loss of life.

The Magic of Reason

Reginald Scot stood up in a time when few dared to, using reason to fight the fear and hysteria that gripped Europe. The Discoverie of Witchcraft wasn’t just a book about witches—it was a manifesto for critical thinking. Scot’s work reminds us that fear and superstition thrive in the absence of knowledge, and that the real magic is found in questioning the world around us.

Today, Scot’s work remains a cornerstone in both the history of magic and the broader history of critical thinking. Whether we’re dealing with ancient superstitions or modern myths, Scot’s message rings true: don’t be fooled—always seek the truth.

Conclusion

Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft is one of the most significant early works to challenge superstition, offering a bold, rational voice in an age of fear and witch hunts. Though the book faced censorship and backlash, its ideas endured, shaping the way we think about magic, witchcraft, and the power of reason. Today, Scot’s work is not only an essential part of magical history but also a lasting reminder of the importance of skepticism and critical thought in the face of ignorance.