A Spud-tacular Journey: The Incredible History of the Potato

Can you imagine a world without crispy french fries, creamy mashed potatoes, or satisfying potato chips? Sounds like a nightmare, doesn’t it? The potato is so ingrained (pun intended) in our daily lives that it’s almost unthinkable that for most of human history, no one outside South America even knew it existed. Yet this humble tuber had to travel across oceans, face suspicion, and even survive being called the “devil’s apple” before becoming a worldwide superstar. Let’s embark on a journey through the ages to discover how the potato, once a mysterious crop from the Andes, conquered the globe and became a beloved staple.

Ancient Potato Roots

Our story begins nearly 10,000 years ago in the Andes Mountains of what is now Peru and Bolivia. Long before Europeans even knew America existed, indigenous people were cultivating wild ancestors of the potato. By 8,000 BC, these early farmers had domesticated potatoes and developed different varieties. The harsh climate of the Andes was perfect for potatoes, which thrive at high altitudes where other crops struggle. For these early civilizations, the potato was more than just food; it was essential to their survival in an environment where farming other crops was nearly impossible.

These ancient Andean people, who later became the mighty Inca civilization, didn’t just eat fresh potatoes. They developed a freeze-drying method that allowed them to store potatoes for years, crucial during famines or long journeys. This freeze-dried product, called chuño, was made by leaving potatoes out in the freezing nights, then thawing and stomping them to squeeze out moisture. This process was repeated until the potatoes were completely dried. Chuño was so vital to the Inca that they considered it one of their most important survival tools, alongside their famed engineering feats like aqueducts and suspension bridges.

The Inca revered the potato so much that they had a potato goddess named Axomama, believed to bring bountiful harvests. They even used potatoes as a timekeeping device—boiling them and timing how long it took to cook them to measure time.

Potatoes Cross the Atlantic

While the Incas thrived on their freeze-dried potatoes, Europeans were still unaware of this underground treasure. It wasn’t until after Christopher Columbus stumbled upon the Americas in 1492 that the potato’s journey to global fame began. The Spanish, who explored South America in the 1530s, encountered the potato during their conquests of the Inca Empire. Initially, they didn’t see the potato as anything special, as they were more focused on gold than tubers.

The first potatoes arrived in Spain around 1570, but instead of causing a culinary revolution, they were met with indifference. Europeans, accustomed to grains and bread, didn’t know what to do with this strange vegetable. Potatoes were initially grown as ornamental plants, valued more for their flowers than their edible tubers. It wasn’t until the Spanish realized the potato’s medicinal properties—that it was believed to cure everything from indigestion to tuberculosis—that people began to take them more seriously.

Sir Walter Raleigh, the English explorer, is said to have introduced potatoes to Ireland but mistakenly served the leaves instead of the tubers. His guests were not impressed (and probably a bit ill), illustrating the potato’s rocky start in Europe.

The Devil’s Apple?

At one point in history, people actually feared potatoes. The potato belongs to the nightshade family, which includes some poisonous species like belladonna and henbane, often associated with magic and sorcery. Many believed potatoes were dangerous or cursed due to their underground growth and vegetative reproduction, which seemed unnatural and sinister.

In parts of Europe, particularly France and Germany, potatoes were called the “devil’s apple,” with fears they could cause leprosy or madness. Early European growers also made the mistake of eating the toxic leaves, which contributed to the potato’s bad reputation. As a result, the potato struggled to gain acceptance.

French scientist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, imprisoned during the Seven Years’ War and forced to eat potatoes, became a key figure in changing public opinion. He promoted potatoes by placing guards around his fields to make them seem valuable, sparking curiosity and acceptance among the French.

Ireland's Love Affair with the Potato

While the potato struggled in most of Europe, it found a welcoming home in Ireland. By the early 1600s, potatoes were introduced to the island, and Ireland’s cool, damp climate proved ideal for growing them. Potatoes thrived in the rocky soil, producing high yields and making them a perfect solution for feeding large families in rural Ireland.

As potatoes became popular, Ireland’s population grew rapidly. By the 18th century, potatoes had become the primary food source for most of the Irish population, especially the poor. They were filling, nutritious, and easy to grow—even on small plots of land. However, this reliance on a single crop led to disaster. The potato blight of the 1840s devastated crops, causing the Irish Potato Famine that killed over a million people and forced another million to emigrate.

During the famine, the average Irish laborer consumed about 10 pounds of potatoes daily—nearly 60 medium-sized potatoes. That’s dedication to your spuds!

Potatoes Save the Day in Europe

The potato’s reputation in Europe changed in the 18th century when famine and food shortages became more common. European governments began promoting the potato as a solution to hunger. In the 1770s, with grain supplies running low, people turned to the potato, finding it was indeed edible.

The potato’s ability to grow in poor soil and produce large quantities of food quickly made it essential for Europe’s growing population. In France, Antoine-Augustin Parmentier became a national hero for advocating potatoes. In Germany, King Frederick the Great ordered his people to plant potatoes, even threatening penalties for noncompliance.

By the 19th century, the potato had become a staple across Europe, especially in the north, where it played a key role in fueling the Industrial Revolution.

Frederick the Great of Prussia used the same clever trick as Parmentier to promote potatoes (or maybe Parmentier used the same trick as King Frederick). He planted them in royal fields and stationed guards, making the crop seem valuable. His subjects, intrigued by the guarded fields, began stealing potatoes to plant in their own gardens, leading to widespread adoption.

(1886) Robert Warthmüller

The Potato Comes to America

Meanwhile, in North America, the first known potato planting occurred in 1719, when Scotch-Irish immigrants brought the crop to Londonderry, New Hampshire. Potatoes gradually spread across the colonies and became important during the California Gold Rush, providing sustenance to thousands of prospectors. Irish immigrants also contributed to the potato’s popularity in American cuisine.

Thomas Jefferson is credited with popularizing french fries in America. After serving as an ambassador to France, Jefferson brought the recipe for “pommes frites” back to the U.S. and served them at a White House dinner in the 1800s.

The Potato’s Worldwide Adventure

By the 18th and 19th centuries, potatoes had spread to Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Islands. They adapted well to new environments, providing a valuable food source in areas where other crops struggled. In China, potatoes became a staple in northern regions, and today, China is the world’s largest producer of potatoes. In India, the potato, introduced by the British, became essential in dishes like samosas and curries. Similarly, in Africa, potatoes thrive in cooler highland regions.

In the 18th century, sailors used potatoes to prevent scurvy, a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C. Potatoes, high in vitamin C, were a crucial part of long sea voyages and could be stored for extended periods without spoiling.

The Modern Potato

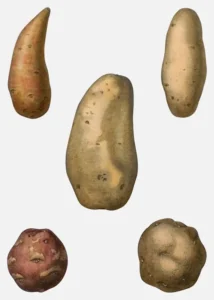

Today, the potato is a global superstar, the fourth-largest food crop worldwide, after rice, wheat, and corn, and feeds more than a billion people daily. Modern farming has produced hundreds of potato varieties, each suited to specific climates and dishes. Countries like China, India, Russia, and the U.S. are major producers, but the potato’s appeal extends far beyond these nations. In Peru, where the potato originated, more than 4,000 varieties are grown, and National Potato Day is celebrated annually on May 30th.

The potato has even ventured into space! In 1995, NASA grew potatoes in space aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia, exploring how to grow food in zero gravity. Potatoes were chosen for their nutritional value, calorie density, and ease of growth.

Potatoes were the first vegetable grown in space! In 1995, NASA successfully cultivated them aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia to test sustainable food sources for space missions. So, if we colonize Mars, potatoes might be on the menu!

Why Potatoes Matter

Potatoes are one of the most versatile foods on the planet. You can fry, mash, roast, boil, or even turn them into vodka. They’re packed with vitamins, minerals, and fiber, making them a healthy and filling option. A single potato contains more potassium than a banana and is rich in vitamin C, B6, and iron. They also require less water than many other crops and produce more food per acre than rice, wheat, or corn.

From the Incas who worshipped the potato to scientists growing spuds in space, the potato has played an essential role in human history. It has fed empires, fueled revolutions, and survived being called the devil’s apple. Today, it continues to be a staple worldwide, proving that sometimes the simplest things in life can have the most profound impact.

In 2008, the United Nations declared it the “International Year of the Potato” to highlight its importance in feeding the world’s growing population. The UN praised the potato as a key player in the fight against hunger and poverty.

Conclusion: A Spud for the Ages

So, next time you enjoy crispy fries, buttery mashed potatoes, or a bag of chips, appreciate the long, strange journey this humble tuber has taken. From ancient Andean highlands to space missions and global kitchens, the potato has proven itself more than just a side dish. It’s a symbol of innovation, survival, and, of course, deliciousness. Whether baked, fried, or mashed, the potato is a true spud for the ages, with a story for the history books.

The cover image: Potatoes grow big in Iowa (1908) by William H. Martin. Public domain.