Extinct Animals of the Public Domain: A Journey Through Time

Ever wondered what the world was like before humans started making themselves at home? Spoiler alert: it was full of some pretty wild creatures, many of which no longer walk (or fly or slither) among us. Thanks to old drawings and the occasional fossil, we can still peek back at these long-lost species and marvel at just how diverse life on Earth used to be. From the Thylacine to the Giant Ground Sloth, these animals had fascinating lives—and equally dramatic exits. So, let’s travel back in time and meet some of the most unforgettable creatures that didn’t quite make it to the 21st century.

The Thylacine: The Lost Apex Predator

The Thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, had it all: fierce stripes, a powerful jaw, and a kangaroo-style pouch. Native to Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea, this carnivorous marsupial looked like a weird mix between a dog and a tiger but wasn’t closely related to either. It was a marsupial through and through, carrying its young in a pouch like its distant cousin, the kangaroo. In fact, both male and female Thylacines had pouches—a fun twist on your average marsupial.

Beyond just looking cool, the Thylacine was crucial to its ecosystem, preying on animals like wallabies, kangaroos, and birds. But the moment European settlers arrived in Tasmania, it was bad news for the Thylacine. Settlers blamed the animal for livestock attacks (whether it was true or not) and put bounties on its head. Add in habitat loss and a mysterious disease, and by 1936, the last known Thylacine died in captivity at the Hobart Zoo.

Despite being extinct for almost a century, sightings of Thylacines are still occasionally reported in the wild. While most are dismissed, these reports keep the legend alive. Plus, scientists have tried cloning the Thylacine using DNA from preserved specimens—but so far, no Jurassic Park moment.

The Dodo: A Symbol of Extinction

Ah, the Dodo. This chubby, flightless bird with a funny beak was the ultimate island dweller, living carefree on Mauritius with no natural predators. First spotted by Dutch sailors in 1598, the Dodo quickly became an easy meal for humans and their invasive pets, like pigs and rats. These hungry invaders destroyed the Dodo’s nests and ate the eggs, making it impossible for the birds to bounce back. By 1662, the Dodo was officially wiped out.

The bird’s strange appearance (imagine a bowling pin with a beak and feathers) led many people to believe it was a mythical creature. However, as scientists began to understand extinction, the Dodo became the poster child for species lost to human activity. Today, the bird stands as a stark reminder of how quickly human presence can turn an entire species into a memory.

In 2005, scientists discovered a mass grave of Dodo bones on Mauritius, giving them more insight into how this bird lived and died. And while it’s extinct, the Dodo remains a pop culture icon, popping up in everything from Alice in Wonderland to memes about bad decisions.

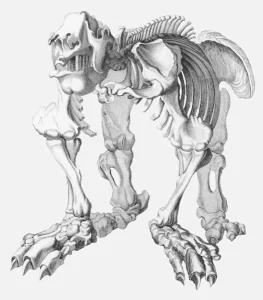

The Giant Ground Sloth: A Colossus of the Past

If today’s sloths are the chill beach bums of the animal kingdom, their ancient cousin, the Giant Ground Sloth, was a lumbering behemoth. Some species could grow up to 20 feet long and weigh several tons! These massive sloths roamed the Americas until about 12,000 years ago, munching on leaves and fruits. Unlike the slow-motion tree-dwellers we know today, the Giant Ground Sloth spent its time on solid ground and could even stand on its hind legs to reach food high up in the trees.

Scientists have found fossils of these mega-sloths all over the Americas, with some even showing signs of having been hunted by early humans. Though climate change likely played a role in their extinction, human hunting was also a big factor. Their fossils provided scientists with their first look at prehistoric megafauna, kickstarting the study of ancient giant animals.

A species of Giant Ground Sloth called Mylodon was so huge and hairy that for years, people believed it still existed in remote caves in South America. Even in the late 19th century, explorers were still finding sloth hair preserved in the dry cave air!

The Jamaican Petrel: An Unsolved Mystery

While some extinct animals are firmly lost to history, the Jamaican Petrel might still be hiding somewhere in the Caribbean. This small seabird hasn’t been officially seen since 1879, but it hasn’t been declared extinct either. Known for its nocturnal lifestyle and shy nature, the Jamaican Petrel is closely related to the black-capped petrel and is thought to nest in burrows, making it extra hard to study.

The bird’s population began to crash after the introduction of invasive species like rats and mongooses, which ate its eggs and young. Though some researchers still hold out hope that small populations of the bird may be surviving in remote areas, the odds are slim. Despite this, the Jamaican Petrel’s story reminds us of how tricky it is to conserve species we can barely find.

The Jamaican Petrel’s call is so rare that if it’s still out there, scientists might have more luck finding it by listening for its haunting cry at night rather than catching a glimpse of its elusive feathers.

The North Island Giant Moa: A Colossal Flightless Bird

The North Island Giant Moa, a colossal bird native to New Zealand, was once the tallest bird in the world. Standing up to 12 feet tall and weighing over 500 pounds, the Moa was a flightless bird that roamed New Zealand’s forests and grasslands for thousands of years. It lived in peace with few natural predators, that is, until the Māori people arrived in New Zealand around 1300 AD.

The Moa became a key food source for the Māori, who also used its bones and feathers to make tools, weapons, and clothing. The bird’s large size made it an easy target, and the introduction of Polynesian dogs, which hunted Moa chicks, didn’t help. By the 15th century, the Moa was completely extinct, along with several other Moa species.

The Moa had an unusual digestive system. Instead of chewing its food, it swallowed stones to help grind up tough plant matter in its stomach. Fossils of Moa have even been found with these “gizzard stones” still intact!

Leguatia Gigantea: The Giant Bird of Mystery

Last but certainly not least, we come to one of the strangest creatures on this list: Leguatia gigantea, a giant bird that may or may not have existed. In 1690, French naturalist François Leguat claimed he saw a six-foot-tall bird with white feathers and pink accents on the island of Mauritius. But here’s the twist—no fossil evidence of this bird has ever been found, making it one of the great mysteries of the animal kingdom.

Some scientists believe Leguat simply mistook flamingos for this mysterious bird since flamingos were known to live on the island at the time. However, not everyone is convinced. Even notable scientist Walter Rothschild, who wrote Extinct Birds in 1907, believed there could be some truth to the tale. Whether it was real or a case of mistaken identity, Leguatia gigantea highlights how myths and legends can spring up from the exploration of new lands.

Mauritius seems to be a hotspot for strange bird stories. Apart from the Dodo and Leguatia, the island was also home to several extinct species of giant tortoises and a flightless rail bird, which disappeared after humans arrived.

The Role of Historical Illustrations in Conservation

While fossils give us the bones, historical illustrations give us life. They allow us to visualize how extinct animals might have looked in the wild—from the intricate stripes of the Thylacine to the stout, quirky form of the Dodo. These illustrations are more than just pretty pictures; they’re windows into the past, helping us appreciate the beauty and uniqueness of creatures that no longer exist.

But they’re also cautionary tales. These images remind us that extinction is forever. Once a species is lost, it’s gone for good, leaving behind only drawings and memories. The animals in these illustrations—whether they were hunted to extinction, wiped out by disease, or fell victim to habitat destruction—are no longer with us. And while they can’t be brought back, they continue to inspire us to protect the species that are still here.

Conclusion: A Call for Conservation

The stories of the Thylacine, the Dodo, the Giant Ground Sloth, the Jamaican Petrel, the North Island Giant Moa, and the enigmatic Leguatia gigantea aren’t just tales of the past; they’re warnings for the future. As humans continue to alter the natural world through deforestation, climate change, and overhunting, we must remember the species we’ve already lost. Each one played a vital role in its ecosystem, and when one species disappears, it can throw the entire balance of nature off-kilter.

By studying these extinct animals, understanding their stories, and reflecting on how they were lost, we can work toward a future where today’s animals aren’t just preserved in pictures. Let’s strive to protect the biodiversity that remains and prevent more species from vanishing forever.