Sea Monsters of the Public Domain: Unleashing the Kraken of Curiosity

Imagine plunging into the mysterious depths of history and surfacing with something truly monstrous. Thanks to the wonders of the public domain, we have a treasure trove of 16th-century sea monsters swimming back into our imaginations. These fantastical creatures, preserved in ancient illustrations, are like a treasure chest washed ashore, just waiting to be opened by curious minds and lovers of myths. But be warned, what you find inside might just make your spine tingle—or, at the very least, give you a good laugh.

The Legendary Origins: Historia Animalium

Before diving into these sea beasts, let’s talk about the source: Historia Animalium, a five-volume collection published between 1551 and 1558 by a man named Conrad Gessner. Gessner was no ordinary scholar—he was a Swiss polymath, physician, and zoologist who had a passion for cataloging every living thing. If Wikipedia had existed back then, Gessner would’ve been its most active editor, constantly updating facts about animals, real or imagined.

At a whopping 4,500 pages, Historia Animalium was groundbreaking for its time. Gessner’s approach was unique, blending credible sources with fantastical creatures, making the book both a serious scientific text and a collection of curious myths. It was a time when science and folklore often mingled, and Historia Animalium offered a peek into a world where reality and imagination weren’t always so neatly separated.

Mythical Creatures: Fact or Fiction?

Now let’s get to the heart of the matter—the sea monsters themselves. Some of these creatures may have been inspired by real animals encountered by sailors, while others were pure products of imagination. Either way, these monsters were part of a world where the unknown stretched beyond the horizon, and every strange sighting came with a good story. But whether they were real or imagined, the creatures documented by Gessner have sparked curiosity for centuries.

The Sea Bishop: A Holy Fish Tale

One of the strangest creatures to emerge from the depths of Historia Animalium is the Sea Bishop, a creature that, according to legend, was pulled from the Baltic Sea in 1531. The story goes that it was presented to King Sigismund I of Poland and a group of Catholic bishops. Instead of being frightened, they were intrigued by the fish-like creature with human-like features. According to the tale, the Sea Bishop made a gesture as if to ask for its return to the sea, and the bishops, feeling rather charitable, obliged.

The story was recorded by French naturalist Guillaume Rondelet, who, to be fair, admitted he heard it secondhand. Even so, the Sea Bishop made its way into Gessner’s Historia Animalium. Whether real or mythical, it was too good of a tale for Gessner to pass up. The creature represented the perfect mix of faith and fear—an odd combination that fascinated people of the time. Some believed the story symbolized divine intervention, while others took it as an exaggerated fisherman’s tale. Either way, it left a lasting impression on the world of sea monster lore.

In later years, skeptics suggested the Sea Bishop might have been a misidentified marine animal like a ray or even an early case of a hoax. But as with many historical sea monsters, the exact truth remains as murky as the waters it came from.

The Sea Monk: A Creature of the Cloth?

Not to be outdone, the Sea Monk is another mysterious creature sighted in 1546 off the coast of Denmark. Described as resembling a monk—with a face, robe, and all—the creature sparked a great deal of interest and confusion. Was it a real animal? Some speculated it could have been a giant squid, an angelshark, or even a walrus. Others believed it was something much stranger.

As with the Sea Bishop, some theorized that the Sea Monk could have been a hoax. There was a practice at the time where fishermen dried out rays or skates, shaping them into strange “monsters” called Jenny Hanivers. While this may explain some sightings, the Sea Monk’s legend persisted in part because it played into the era’s fascination with the ocean’s unknown depths.

The Sea Monk continued to capture imaginations for centuries, appearing in various artworks and accounts. Some artists even gave it a habit-like hood, further blurring the lines between monk and monster. Whether it was a real sea creature or a creature of the imagination, the Sea Monk remains one of the more enduring legends of the sea.

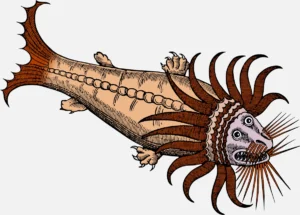

The Rubus: A Fish Full of Spikes

The Rubus was a strange fish that Gessner described as being sighted between Antibes and Nice in 1562. According to his account, this creature was round, with many red spots, sharp fins, and covered in spikes. Gessner wrote that the Rubus was a slow swimmer due to its large size, but it made up for its sluggishness with a cunning hunting strategy. The Rubus would settle on the seafloor and wait for unsuspecting prey, then bury its catch in the sand before devouring it.

Despite its fierce appearance and hunting technique, Gessner mentioned that the Rubus was actually considered quite delicious by those brave enough to catch it. This adds a humorous twist to its otherwise intimidating description—a reminder that even the most dangerous-looking sea creatures could end up on the dinner table in the 16th century.

The Rubus serves as a fascinating example of how both fear and practicality shaped human interactions with the unknown creatures of the sea. While terrifying in theory, it seems even the Rubus couldn’t escape becoming part of a good seafood recipe.

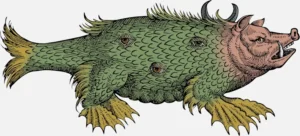

The Sea Pig: A Curious Creation

Among the quirky sea monsters, the Sea Pig stands out for its sheer oddness. First introduced to the public by Swedish cartographer Olaus Magnus in 1539, the Sea Pig appeared in his detailed map of the Nordic countries, Carta Marina. Magnus loved to fill his maps with all sorts of strange creatures, and the Sea Pig was one of his most famous.

The creature, according to Magnus’s description, had the body of a pig, dragon-like feet, boar tusks, horns growing from its back and was dotted with eyeballs, making it a truly bizarre sight to imagine swimming in the deep waters of the north. The oceans, still largely unexplored at the time, seemed like an endless source of mystery, and the Sea Pig fit right in with other legendary monsters of the deep.

While it’s unclear whether the Sea Pig was based on any real animal, its inclusion in Carta Marina spoke to the imaginative spirit of the age. Mapmakers like Magnus filled in the gaps in their knowledge with creative guesses, sometimes turning the ocean into a wild zoo of fantastic creatures. The Sea Pig, whether real or not, is a delightful reminder of how myths shaped early explorations of the natural world.

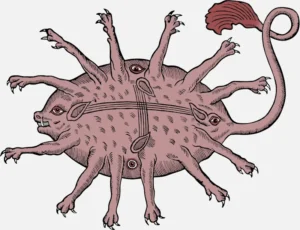

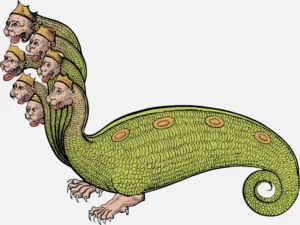

The Hydra: A Mythical Monster of the Seas

The Hydra, though rooted in ancient Greek mythology, found its way into later works of natural history, including Gessner’s Historia Animalium. Known for its many heads and terrifying regenerative ability, the Hydra was said to dwell in swamps and waters, a symbol of both power and danger. According to the legend, if one of its heads was cut off, two more would grow back in its place, making it nearly impossible to kill.

Gessner included the Hydra as part of his collection, not because he believed in its literal existence, but because it represented the unknowable dangers that early sailors and explorers feared. The Hydra was a multi-headed threat that echoed the many perils of the sea—storms, shipwrecks, and mysterious creatures lurking just beneath the waves.

The Hydra may be one of the most legendary of all sea monsters, but it remains a symbol of humanity’s battle with the unknown. Even today, it appears in stories, films, and art as a reminder of how legends can take on a life of their own, continuing to inspire fear and wonder long after the original stories have been told.

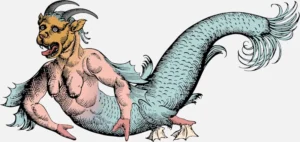

The Sea Devil: The Face of Terror

Finally, we come to the Sea Devil, a creature so menacing that its very name evokes fear. While there are many accounts of sea devils throughout history, Gessner’s description focused on a creature that had the appearance of a peculiar horned lion-woman-fish. With its jagged teeth and menacing eyes, the Sea Devil was said to lurk in the darkest parts of the ocean, waiting to snatch up any unfortunate sailor who strayed too close.

The Sea Devil’s horns and fearsome appearance earned it a notorious reputation among sailors. Many believed it was a physical manifestation of the ocean’s unpredictability and danger. Some accounts even described the Sea Devil as having the power to bring storms or cause ships to wreck, making it both a monster of the deep and a creature tied to natural disasters.

Like the Hydra, the Sea Devil symbolized humanity’s ongoing struggle with the untamed forces of nature. Though more a product of fear than fact, the Sea Devil remains one of the most terrifying sea monsters to emerge from the public domain of old legends.

Why Sea Monsters Matter

So, why do these old illustrations and stories still matter? For one thing, they offer us a window into the past, a time when science was still in its infancy and the world was full of wonder. The 16th century was a period of exploration, with sailors venturing further and further from their homelands. The oceans, largely uncharted and mysterious, were the perfect setting for stories of sea monsters.

But these monsters were more than just scary stories. They reflected the fears and hopes of the people of the time. The ocean, with its vastness and unpredictability, symbolized both danger and opportunity. For explorers, it represented the possibility of discovering new lands and new wealth. But it also held the threat of disaster, with monsters serving as a kind of metaphor for the unknown perils that awaited them.

Sea monsters, like those described in Gessner’s Historia Animalium, continue to capture our imagination because they speak to our desire to understand the unknown. They remind us of a time when the world was still full of mysteries, waiting to be uncovered. And, in a way, they remind us that there are still mysteries out there, waiting for us to dive in and discover them.