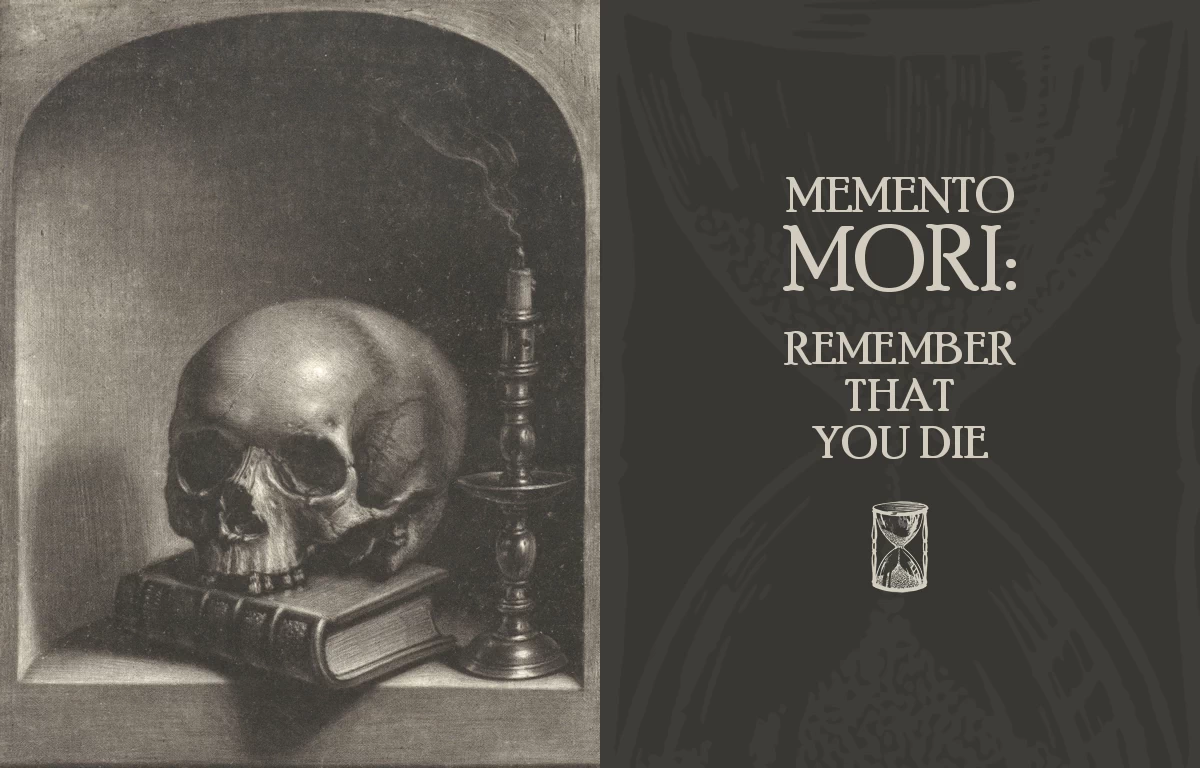

Memento Mori: A Reminder That You’ll Die

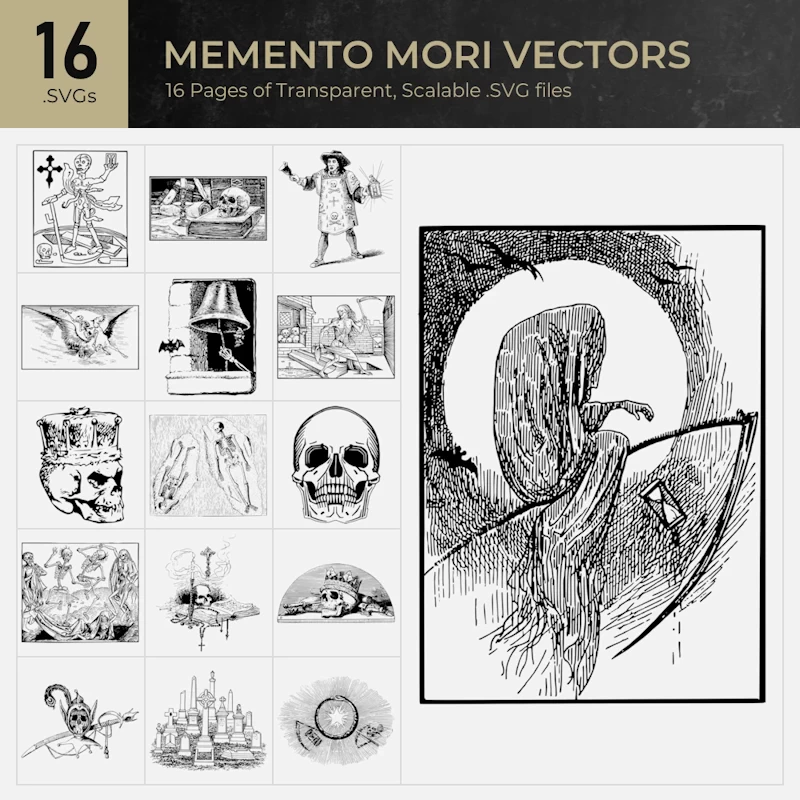

Throughout history, people have found ways to remind themselves of one unavoidable truth: life doesn’t last forever. The Latin phrase memento mori translates to “remember that you must die.” Now, before you think, “Wow, how depressing!”—hold on. It’s not meant to be gloomy. Think of it as a wake-up call to live your best life, knowing it won’t last forever. Philosophers, artists, and writers from across the ages embraced this idea, using it to help people reflect on the briefness of life. So, grab your hourglass and skull (metaphorically speaking), and let’s dive into how memento mori shaped the past—and how it’s still hanging around in today’s world.

How It All Began

The origins of memento mori go all the way back to ancient Rome, where they were no strangers to the idea of human frailty. Picture this: you’re a Roman general, fresh off a big win, parading through the streets like a hero. Behind you, a humble servant whispers in your ear, “Remember, you’re only human, and you will die.” Yeah, talk about a mood killer. Even at the height of their glory, these leaders were reminded that life is fleeting, and no amount of power or fame could make them immortal.

The Romans understood that life’s victories are temporary. Their culture was full of reminders that death was around the corner—whether through public funerals, tomb inscriptions, or the morbidly fascinating gladiator games. These constant reminders weren’t there to depress people but to humble them, encouraging everyone to live with purpose. Later on, this idea found a new audience in the Middle Ages, where memento mori became even more urgent. With so many people dropping like flies (thanks to war, famine, and diseases like the Black Death), it was hard not to think about death. For medieval folks, memento mori wasn’t just philosophical—it was daily life.

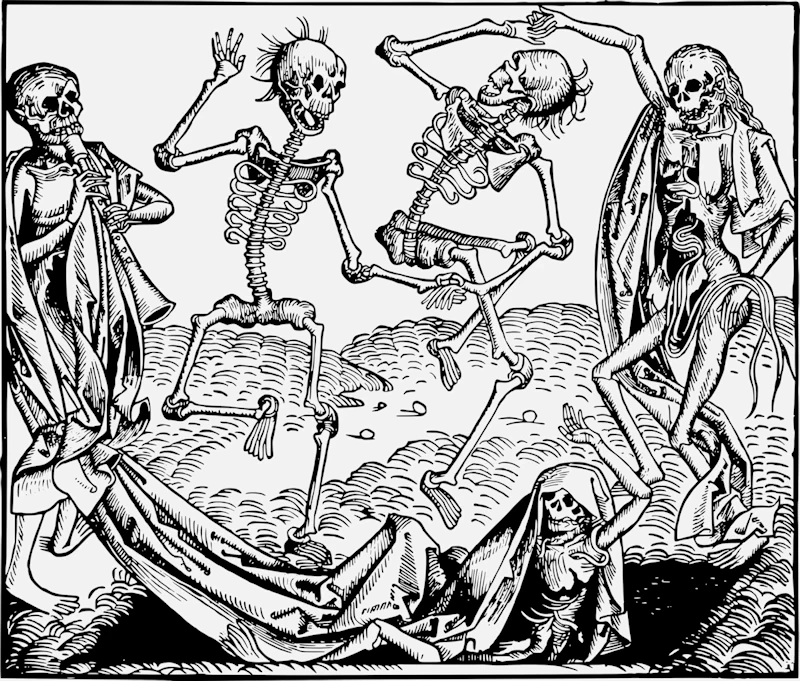

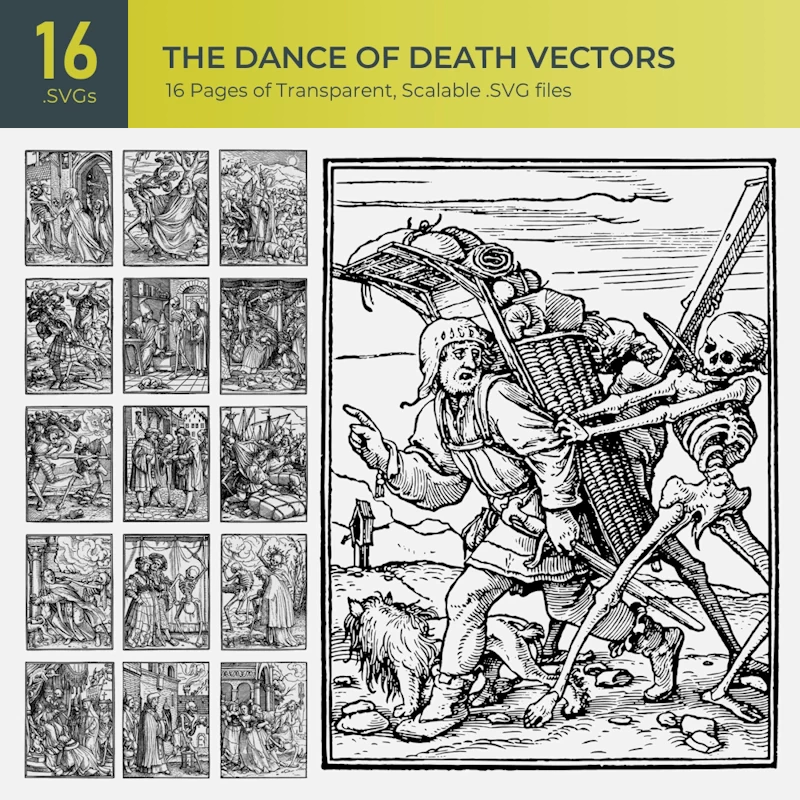

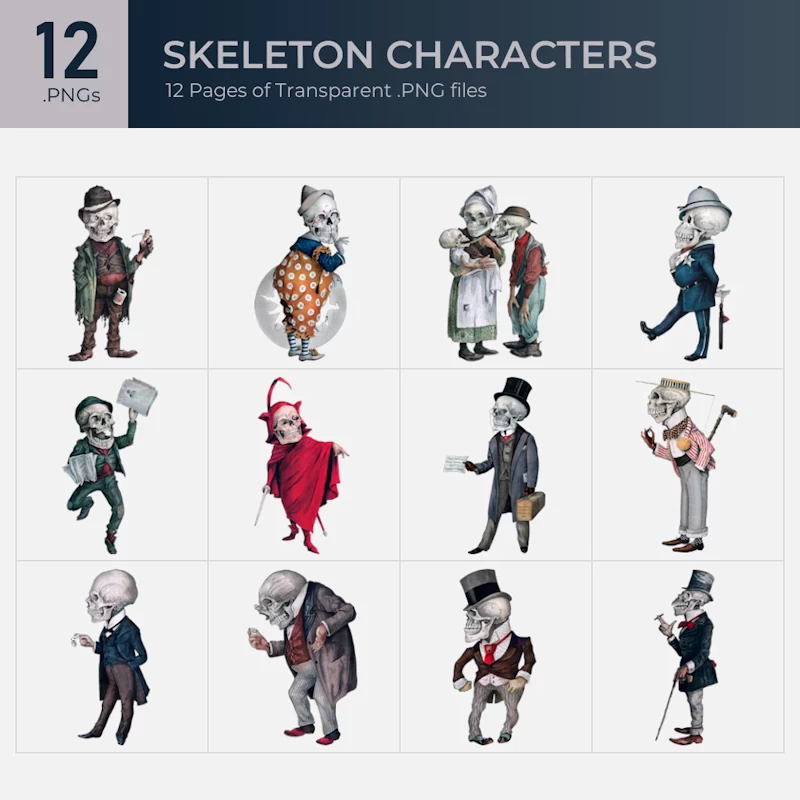

The Dance of Death

One of the most famous expressions of memento mori during the Middle Ages was the “Danse Macabre” or “Dance of Death.” Now, before you imagine skeletons hosting a wild rave, it was actually a serious form of art. This grim dance showed skeletal figures leading people from all walks of life—kings, peasants, even kids—straight to their graves. It was a not-so-subtle reminder that death comes for everyone, no matter your status.

The “Danse Macabre” was often painted in churches, giving worshippers something to think about during mass. These images weren’t just for shock value; they conveyed a deeper message: no one is too important for death’s embrace. While it might sound a little macabre, the intent wasn’t just to scare people but to encourage them to live moral, reflective lives. Whether you were rich or poor, the skeleton was coming for you. And that’s not all—this medieval obsession with death also spawned some interesting art and literature. People began to focus more on the afterlife, believing that how they lived would impact where they ended up when the inevitable came knocking.

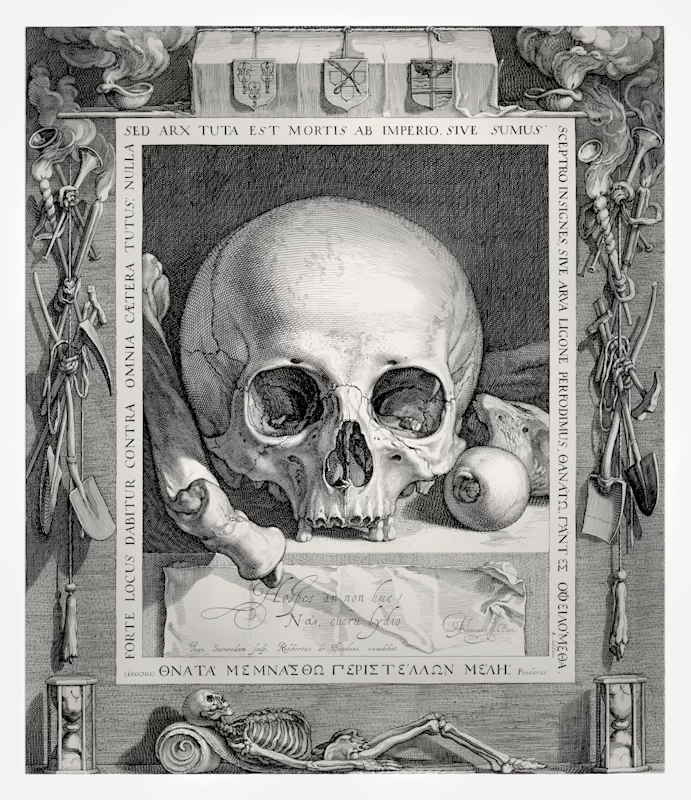

Renaissance and Rebirth... Of Skulls and Hourglasses?

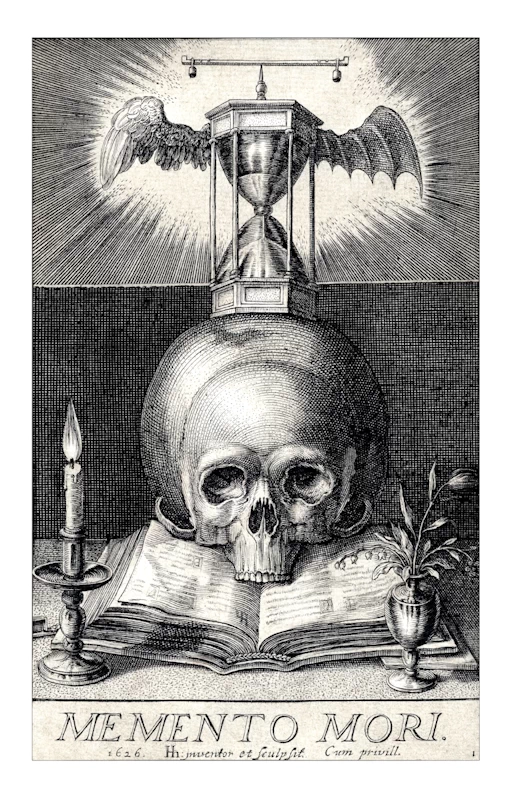

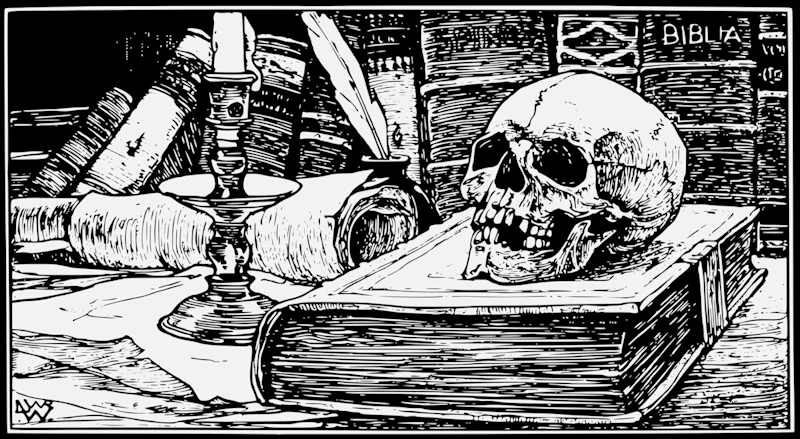

By the time we roll into the Renaissance, humanity is knee-deep in rediscovering old ideas, exploring new philosophies, and creating art that would shape history. So naturally, memento mori fit right in. Renaissance artists and thinkers were fascinated by life, death, and everything in between. They began sneaking little reminders of mortality into their works. Skulls, hourglasses, wilting flowers—these weren’t just random doodles. They were deliberate symbols meant to make you pause and reflect on the fact that life is ticking away.

Take Hans Holbein’s painting “The Ambassadors” (1533), for example. At first glance, it’s just two well-dressed guys showing off their wealth. But look closer, and you’ll spot a weirdly distorted skull at the bottom. When viewed from the right angle, the skull suddenly snaps into focus, giving you a creepy reminder that even in the middle of success, death is always hanging out in the background. It’s a visual nudge to stop taking life too seriously—because, well, we’re all headed for the same fate. Artists during this period loved playing with this balance between life’s beauty and its inevitable end. And the patrons who commissioned these works weren’t exactly subtle about wanting a reminder that they too were on borrowed time.

Hans Holbein (1533)

Hans Holbein (1533)

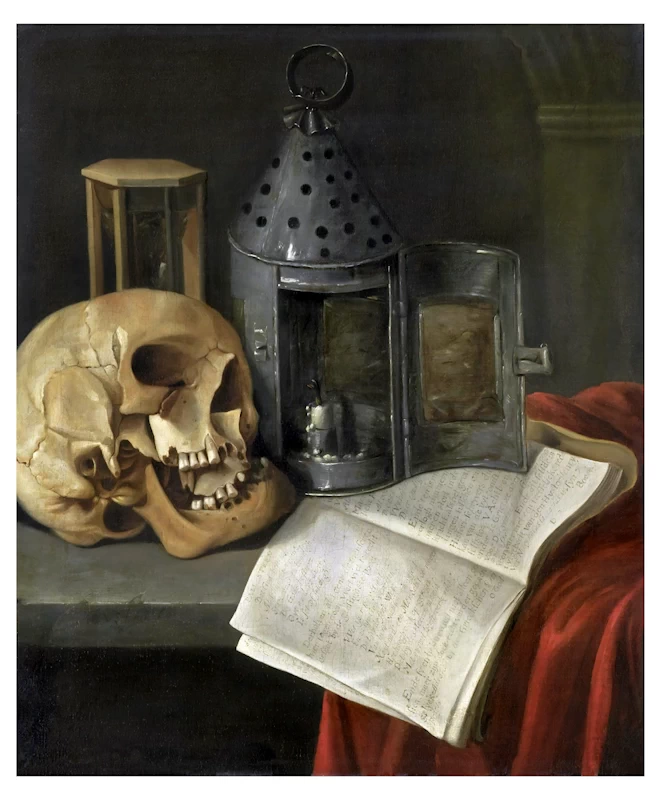

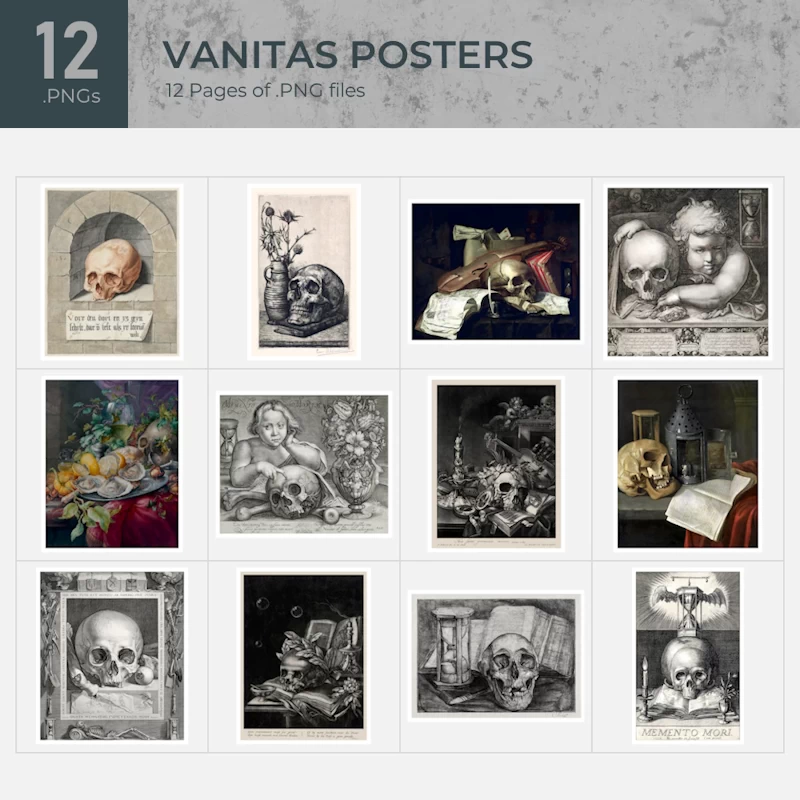

The Dark and Moody Baroque Era

Next up, we have the Baroque period, which was all about big emotions, deep shadows, and dramatic flair. This was when memento mori got a little more theatrical. Artists took the theme and ran with it, creating a style called “vanitas.” Vanitas paintings are like puzzles, filled with symbolic objects that practically scream, “Life is short!” You might see a bowl of perfect fruit, but look closely—one piece is starting to rot. There might be a candle burning, but that flame is about to flicker out. And of course, the ever-present skull, just chilling on the table. It’s a visual reminder that beauty fades, wealth disappears, and death waits for us all.

Two of the masters of vanitas were Pieter Claesz and Harmen Steenwijck, who turned still lifes into meditations on mortality. These paintings weren’t just for decoration; they were conversation starters. Viewers were meant to ponder the deeper meaning behind the ordinary objects. Should you focus on accumulating wealth? Or should you look for something deeper, knowing that none of it will matter when death knocks at your door? It wasn’t just about being gloomy—it was about finding a balance between enjoying life and remembering that it won’t last forever.

Memento Mori in Books and Philosophy

It wasn’t just artists getting in on the action—writers and philosophers were also obsessed with memento mori. Michel de Montaigne, a French philosopher in the 16th century, practically made a career out of writing about death. In his Essays (1580), Montaigne argued that thinking about death wasn’t morbid—it was liberating! By accepting that death is a part of life, you’re free to live authentically and without fear. Instead of dreading the end, Montaigne thought we should embrace it as motivation to live fully.

Blaise Pascal, a 17th-century French philosopher, also couldn’t resist diving into the topic in his Pensées. Pascal believed that life was short and unpredictable, and because of that, we needed to be prepared for what comes next—especially in terms of our faith. For Pascal, memento mori wasn’t just about accepting death; it was about making sure you were ready for eternity. Heavy stuff, right? But these thinkers weren’t trying to depress anyone. They were encouraging people to live more meaningful, reflective lives.

Modern Takes on an Old Idea

Fast forward to modern times, and you might think memento mori is old news. Not so fast! Filmmakers, authors, and artists are still diving into themes of death and mortality like it’s the newest trend. One iconic example is Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal (1957), where a knight literally plays chess with Death while contemplating life’s meaning. Spoiler: Death always wins. But the real point is that facing death forces us to confront the things we usually avoid.

And in the art world, Damien Hirst took memento mori to a whole new level with his piece For the Love of God (2007)—a human skull encrusted with diamonds. Flashy? Yes. But it also makes you think about the strange relationship between wealth and death. No matter how much money or bling you have, none of it can buy you more time on this Earth. Even literature gets in on the action. Books like The Road by Cormac McCarthy and Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro explore the fragile nature of life. These stories make readers pause and reflect on how they’re spending their time, urging them to focus on what truly matters.

Why Should We Care About Memento Mori Today?

So, why does this ancient concept still matter? Well, while we’ve got all kinds of fancy technology and science to distract us, death remains one of life’s constants. No app or breakthrough can change that fact. Memento mori offers a different perspective—it’s not about fear, it’s about clarity. It encourages us to stop worrying about things like status or wealth and instead focus on what’s truly important.

Whether it’s spending time with loved ones, following a passion, or simply enjoying a quiet moment, memento mori reminds us that life is precious. In a world that often pushes us to chase after more—more success, more stuff, more everything—memento mori says, “Hey, slow down. You don’t have forever.”

The Balance Between Life and Death

Memento mori isn’t just about being morbid. It’s about balance—between enjoying life and being mindful that it’s not endless. It’s like walking a tightrope between the present and the inevitable. Living fully means accepting that time is ticking, but instead of letting that scare us, it can inspire us to make the most of every moment.

In the end, the skull, the hourglass, and the wilting flower are there to remind us that while death is a part of life, it doesn’t have to be feared. Embrace it, reflect on it, and let it push you to live a life that’s truly meaningful. Because in the end, that’s all we really have.

One Comment

Comments are closed.