Anna Atkins and the Magic of Cyanotypes: A Story of Science, Art, and Nature

Photography today is everywhere, from selfies to scenic vacation photos, but the art of capturing images goes back a long way—well before phones or even film cameras existed. Back then, photography was a delicate mix of science, patience, and, for those who were really skilled, a bit of artistic flair. Among the earliest pioneers of photography was a woman named Anna Atkins. Though her name may not be as well-known as some other early photographers, her work was groundbreaking. Atkins didn’t just take pictures—she transformed how people thought about photography, blending science, art, and nature in a way that had never been done before.

You might wonder what makes Anna Atkins so special. Well, her main claim to fame comes from her work with a unique photographic process called the cyanotype, a type of image that creates beautiful, bright blue prints. So, who was Anna Atkins, and why are her cyanotypes still important today?

The Life of Anna Atkins

Anna Atkins was born in 1799 in the small town of Tonbridge, England. Her early life was shaped by her family situation. Her mother died when she was only a few months old, leaving Anna to be raised by her father, John George Children. Children, who was a respected scientist, took a different approach to raising his daughter than most parents did back then. He made sure she received a good education, something most girls didn’t have access to in the early 19th century. Anna had the chance to learn about science and the natural world, especially botany.

In her early twenties, Anna already had a reputation for her detailed scientific illustrations. She drew pictures of shells for one of her father’s books, and these drawings were highly regarded for their precision. But she didn’t stop at drawing. As new inventions in photography began to appear in the 1830s and 1840s, Anna became intrigued by the idea of using photography to document the natural world. And that’s where cyanotypes came into the picture.

Understanding Cyanotypes

Cyanotypes were invented by Sir John Herschel, a scientist who discovered this simple photographic process in 1842. They are known for their striking blue color, which is why cyanotypes are sometimes called blueprints. Though today we associate blueprints with architectural drawings, the cyanotype process was initially used more for artistic and scientific purposes.

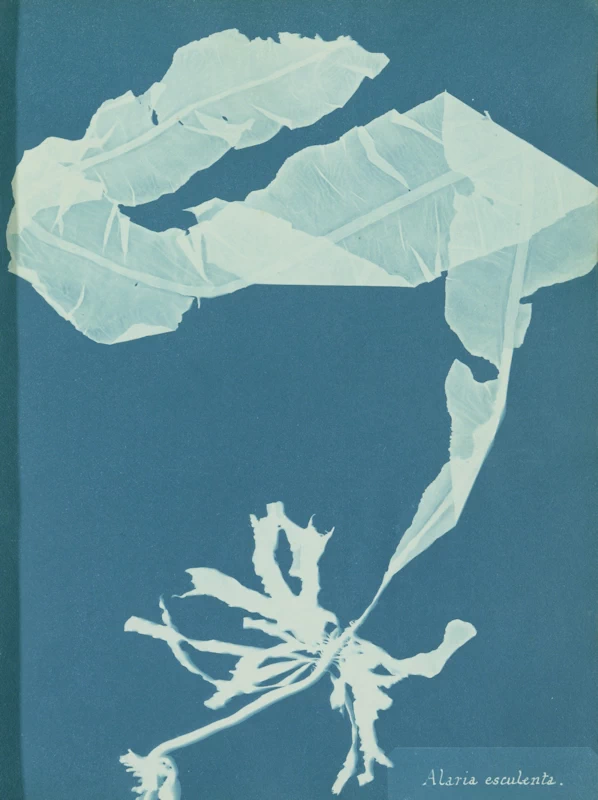

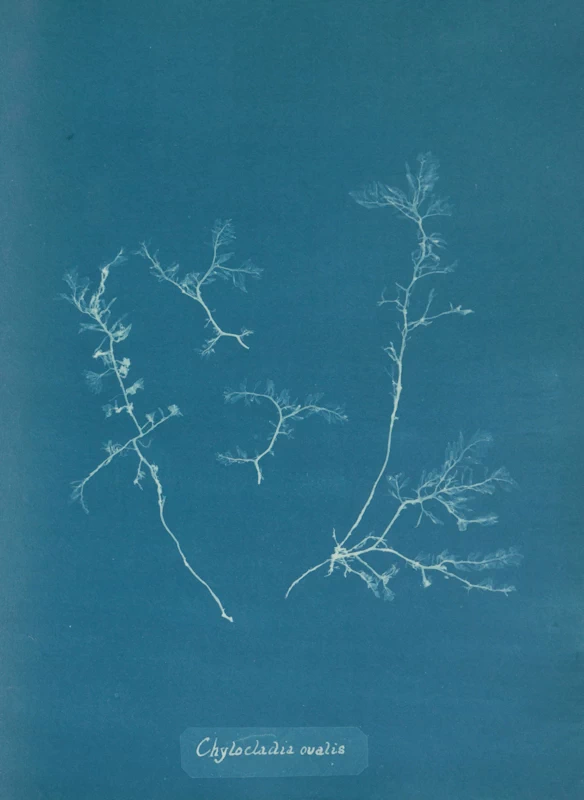

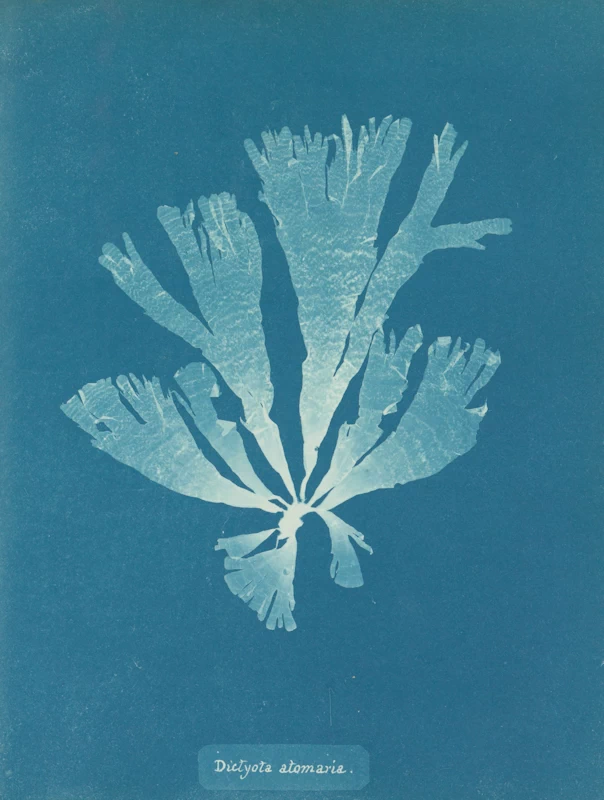

The process of making a cyanotype is fairly straightforward, but it has a touch of magic to it. The first step is applying two chemicals—ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide—to a sheet of paper or fabric. Once these chemicals are combined, the paper becomes sensitive to light. You then place any object directly onto the paper, which block out the light from the areas they cover.

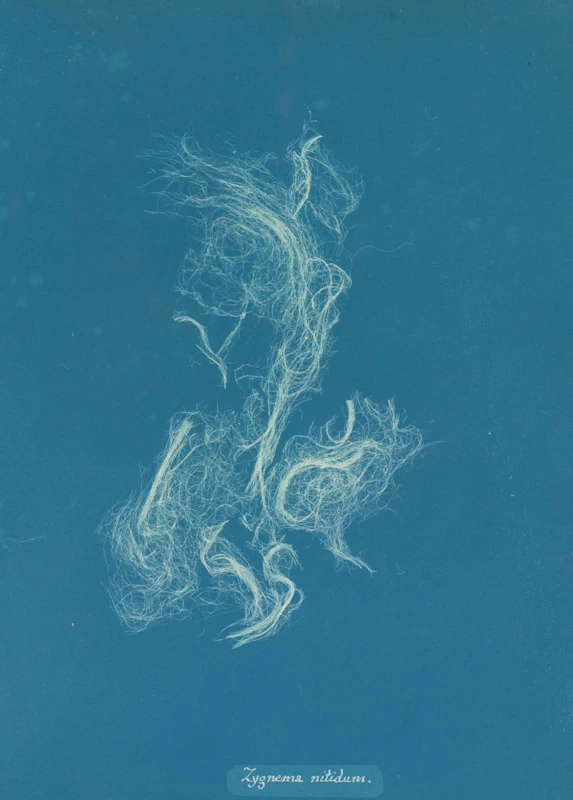

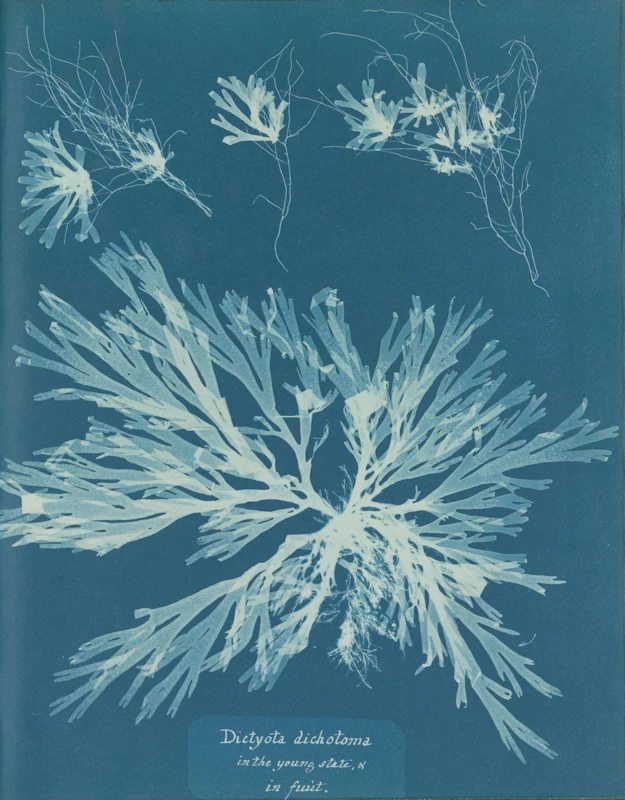

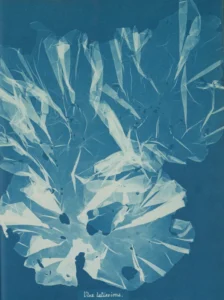

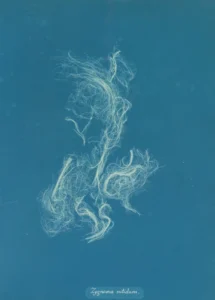

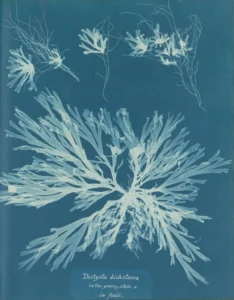

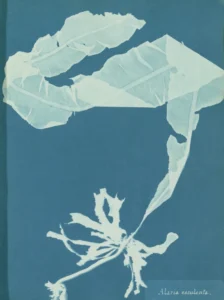

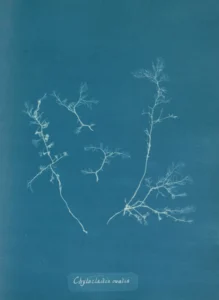

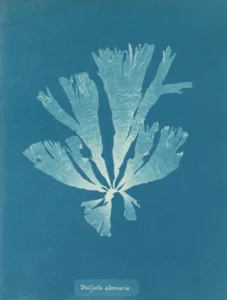

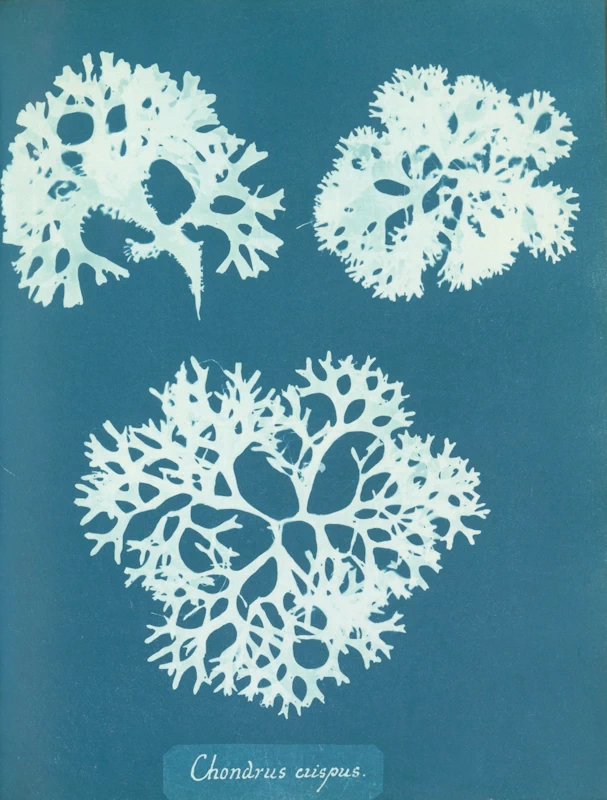

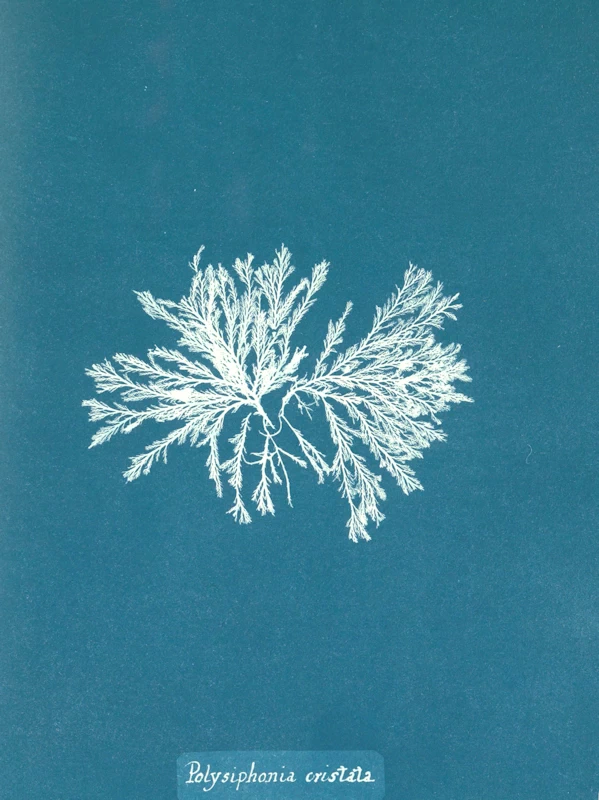

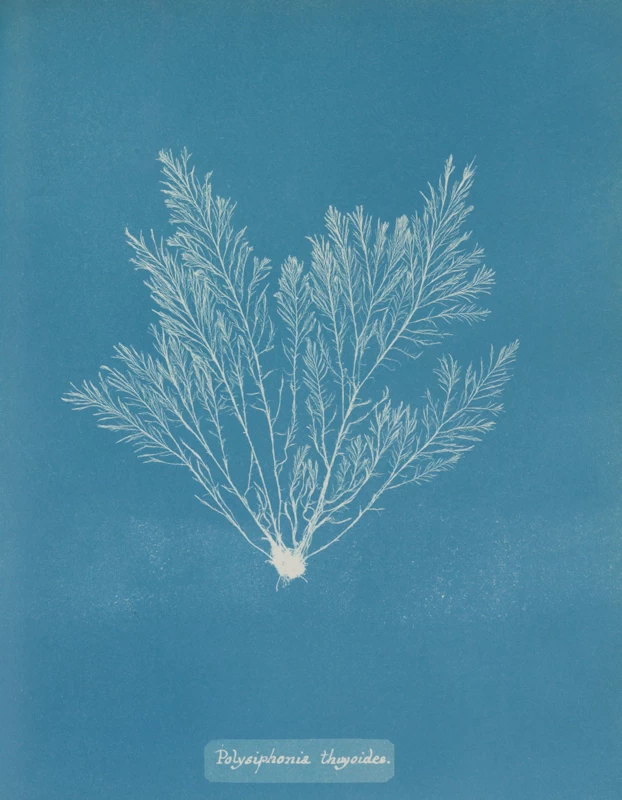

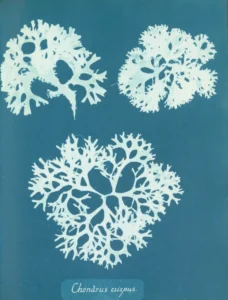

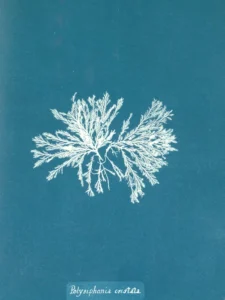

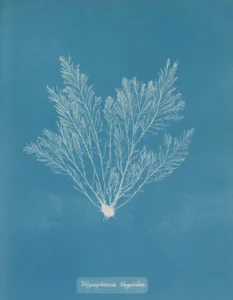

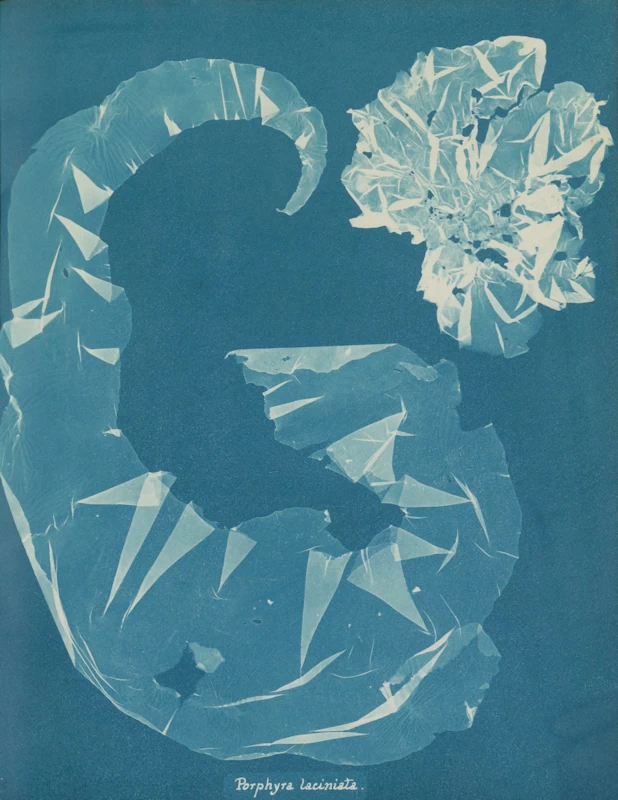

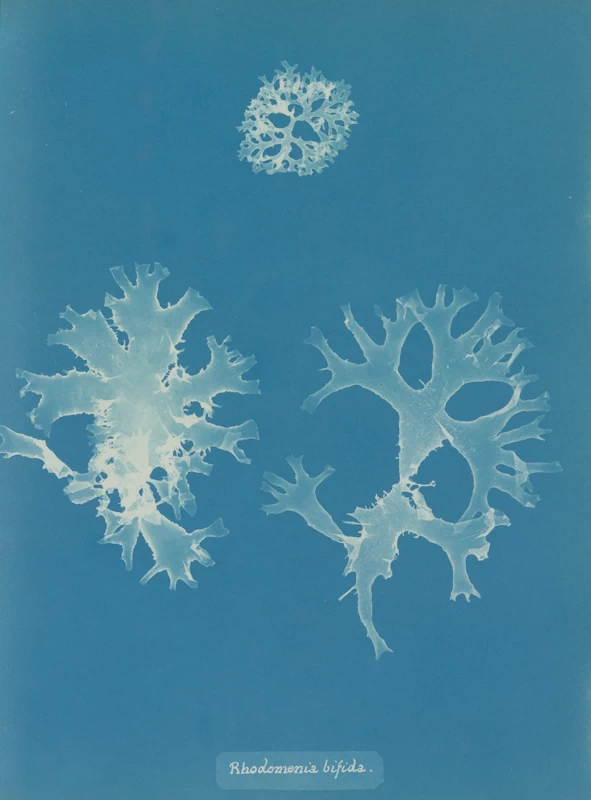

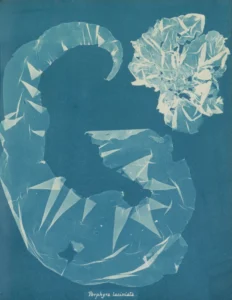

Once everything is in place, the paper is left out in the sun. The sunlight causes a chemical reaction that turns the uncovered areas a rich blue color. After the paper has been exposed long enough, it’s rinsed with water to remove any leftover chemicals. What’s left is an image with the objects in white against a vibrant blue background, almost like a negative image. The cyanotype process creates delicate, beautiful prints that can capture incredible detail.

How Anna Atkins Used Cyanotypes

When Anna Atkins learned about cyanotypes, she saw an opportunity to combine her two passions: botany and photography. In the 1840s, photography was still in its early stages, and very few people were experimenting with it. Atkins decided to use cyanotypes to document different plant species, particularly algae and seaweed, which she had collected over the years.

In 1843, Atkins published Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. This wasn’t just any book—it was the first book ever to be illustrated using photographs rather than drawings or engravings. That’s right, Anna Atkins is credited with creating the first photographic book in history, and she did it using cyanotypes. Her book featured images of various types of algae, showing each plant in precise detail. The book was revolutionary, combining science and photography in a way that pushed the boundaries of both fields.

Anna Atkins’s work matters for several reasons. First, she stood out as a trailblazer for women in both science and photography. In an era when most women weren’t encouraged to participate in these fields, Atkins not only took part—she led the way. Her work demonstrated that women could make significant contributions to the male-dominated worlds of science and technology, even when the odds were stacked against them.

Second, Anna Atkins showed how art and science could come together to create something truly special. Her cyanotypes weren’t just scientific records of plants—they were also beautiful. The vibrant blue color of the prints, along with the delicate details of the plants, created images that were as visually stunning as they were informative. In this sense, Atkins’s work blurred the lines between art and science, reminding us that these fields don’t always have to be separate.

Finally, she used photography to advance science. The cyanotypes she created helped botanists of her time better understand plant species. Her book offered an accurate visual reference for scientists who didn’t have easy access to these plants themselves. This was especially useful in the days before photography became a widespread tool for scientific documentation.

The Lasting Legacy of Anna Atkins

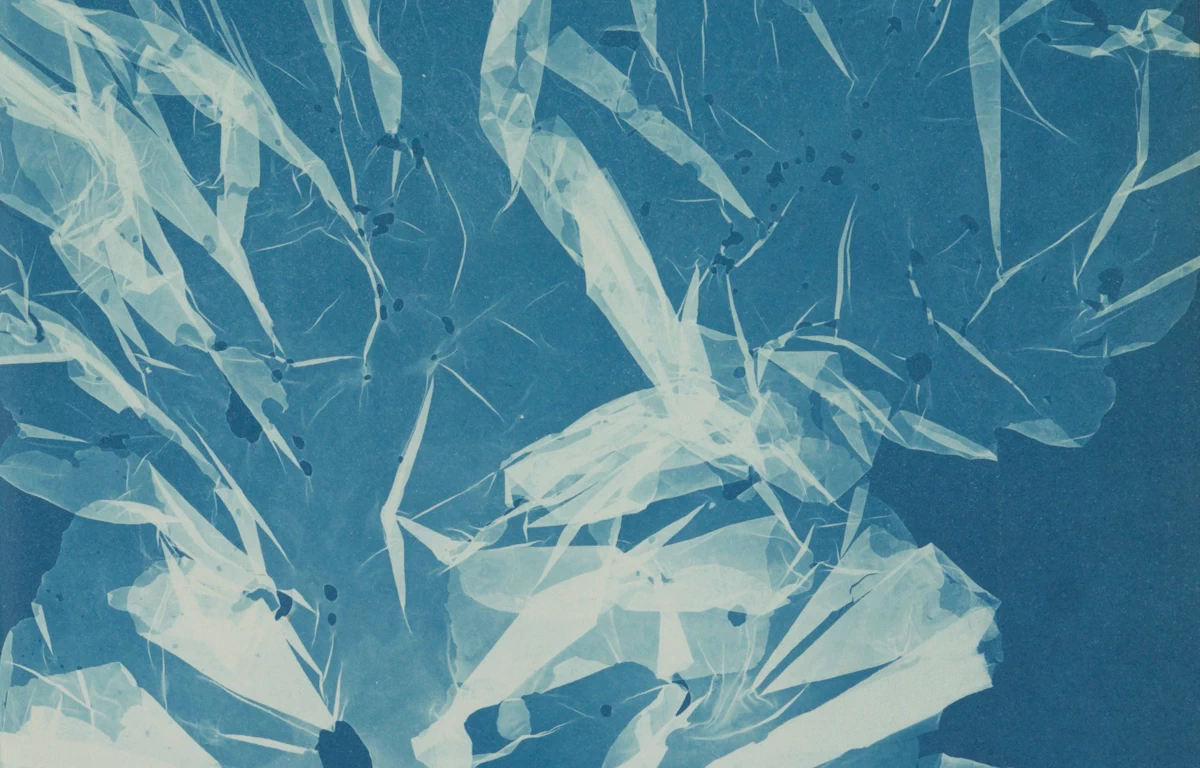

Today, Anna Atkins’s cyanotypes are still celebrated for their beauty and historical importance. They’re displayed in art galleries and museums around the world, where people admire them not just as scientific records but as pieces of art. Her work has inspired generations of artists and photographers who see her cyanotypes as an example of how simple techniques can create something timeless.

Interestingly, the cyanotype process itself has made a bit of a comeback in recent years. Though modern cameras and digital technology have made photography easier and more accessible than ever, many artists are returning to this old-fashioned technique. Cyanotypes have a simplicity that feels refreshing in today’s fast-paced, high-tech world. They give us a chance to slow down and appreciate the beauty of nature in a way that feels almost meditative.

Anna Atkins’s legacy lives on, not just through her cyanotypes but through the way she showed the world that photography could be more than just a way to capture moments. It could also be a tool for exploration and discovery, a bridge between art and science. Through her work, she opened new doors for photographers, scientists, and women alike, leaving behind a body of work that still feels innovative nearly two centuries later.