The Politics of Pattern: William Morris’s Philosophy in Art and Design

When you think of wallpaper, you might not immediately connect it to politics. But for William Morris, a 19th-century artist and designer, every swirling vine, leaf, and flower on his famous patterns carried a powerful message. Morris believed that art was for everyone and that beauty should fill our everyday lives, not just exist in museums and the homes of the wealthy. In his vision, art was a force that could make life richer and society fairer. Morris wove his beliefs about the value of good work, the importance of nature, and his fierce dislike of industrialization into each of his designs.

Who Was William Morris?

Born in 1834 in England, William Morris grew up fascinated by the natural world and stories of the past, especially those about knights and castles. Although he was wealthy enough to live a comfortable life without working, Morris wasn’t content to sit back and relax. He studied at Oxford University, where he met a group of artists and writers who shared his love for art and history. Together, they formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group that pushed back against the dry, realistic art that dominated Victorian England.

Morris believed in creating art that had meaning, beauty, and purpose. He wasn’t interested in flashy, modern trends. Instead, he looked back to the medieval period for inspiration. To Morris, the Middle Ages represented a time when artisans took pride in their work, creating things by hand with patience and care. He wanted to bring back that same spirit of craftsmanship to Victorian England, where mass production was beginning to replace the work of individual artists.

Morris created some of the most famous patterns in design history, from lush floral wallpapers to richly detailed textiles. But his designs were more than decoration; they reflected his political beliefs and his hope for a better society.

Fighting Industrialization with Art

During Morris’s time, England was going through major changes. The Industrial Revolution had transformed nearly every part of society, with factories churning out goods at unprecedented rates. While mass production made items cheaper and more accessible, it also changed how people worked and lived. Instead of making things by hand, skilled artisans were being replaced by machines and assembly lines. Workers faced long hours in harsh conditions, with little chance to use creativity or skill.

Morris saw this shift as a tragedy. He believed that work should be meaningful, something that people could take pride in. He saw factories as dark, dirty places that stripped people of their joy and individuality. To Morris, this system of industrial capitalism—where profit was the priority and workers were treated as little more than cogs in a machine—wasn’t just harmful, it was downright inhumane.

Through his art, Morris tried to push back against this industrial tide. He wanted to prove that well-made, beautiful items could still be produced by hand. In 1861, he founded a design company that created wallpapers, textiles, furniture, and more, all by skilled artisans. By emphasizing craftsmanship and rejecting mass production, Morris hoped to show that quality and beauty were more important than speed and profit.

Nature as Inspiration and Protest

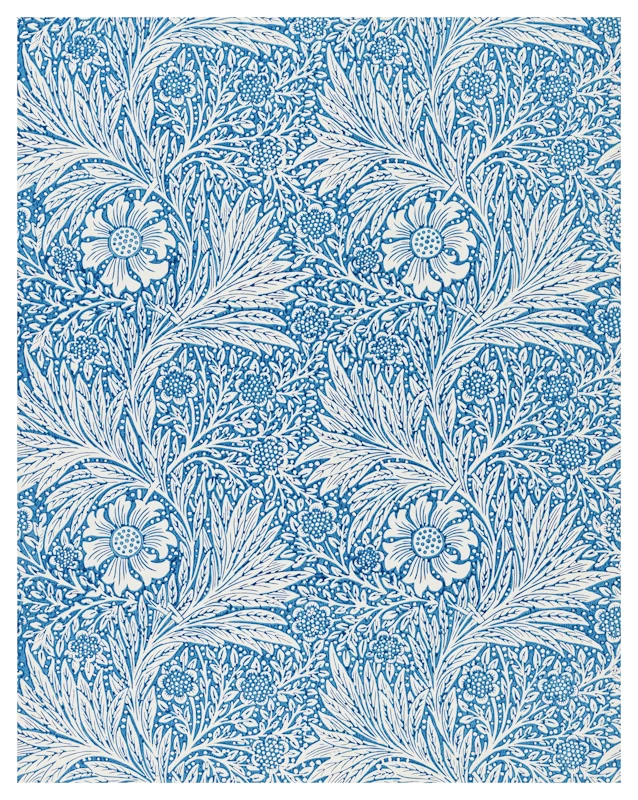

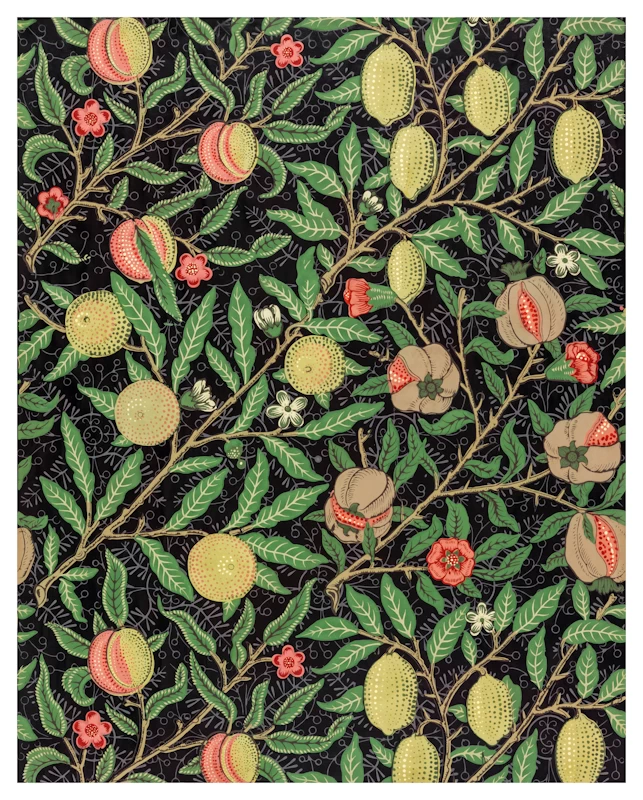

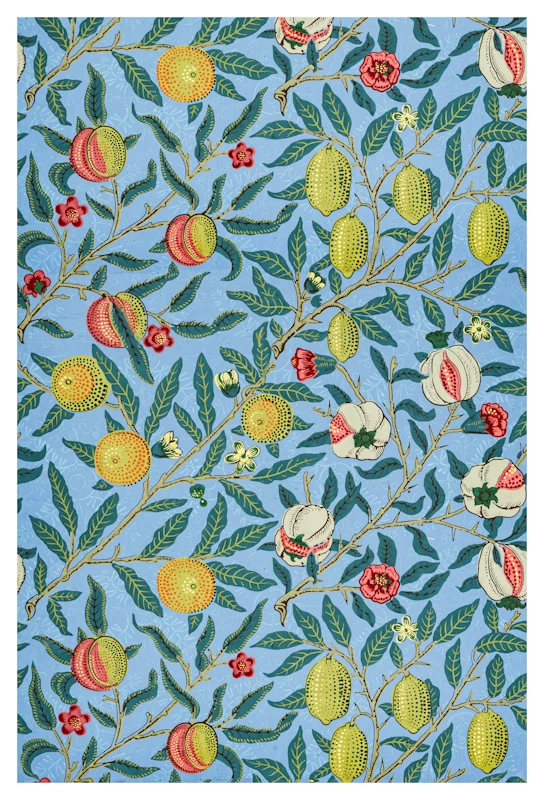

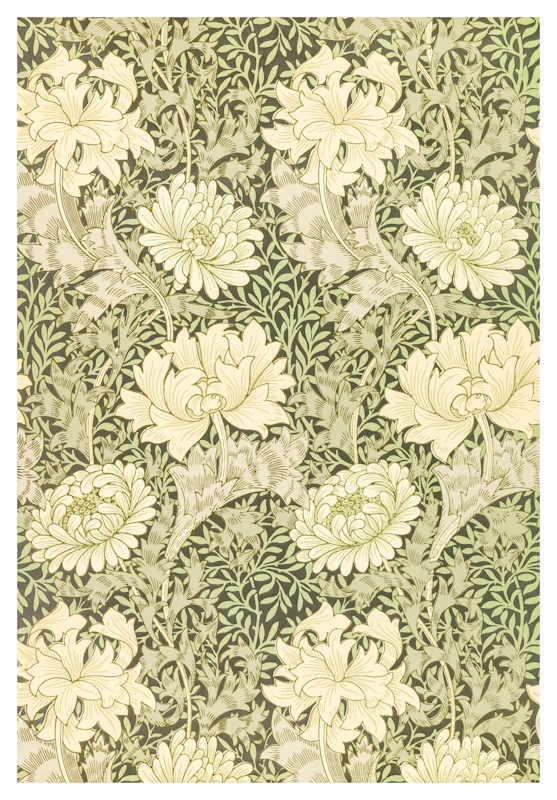

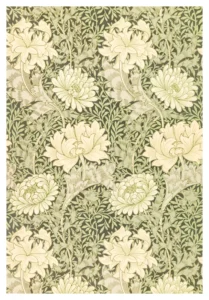

You’ll notice a theme in Morris’s patterns: they’re filled with leaves, flowers, birds, and twisting vines, all inspired by nature. But for Morris, using nature in his art was more than just an aesthetic choice; it was a statement. In an increasingly industrialized world where pollution and cities were rapidly expanding, Morris wanted his patterns to remind people of the beauty and importance of the natural world.

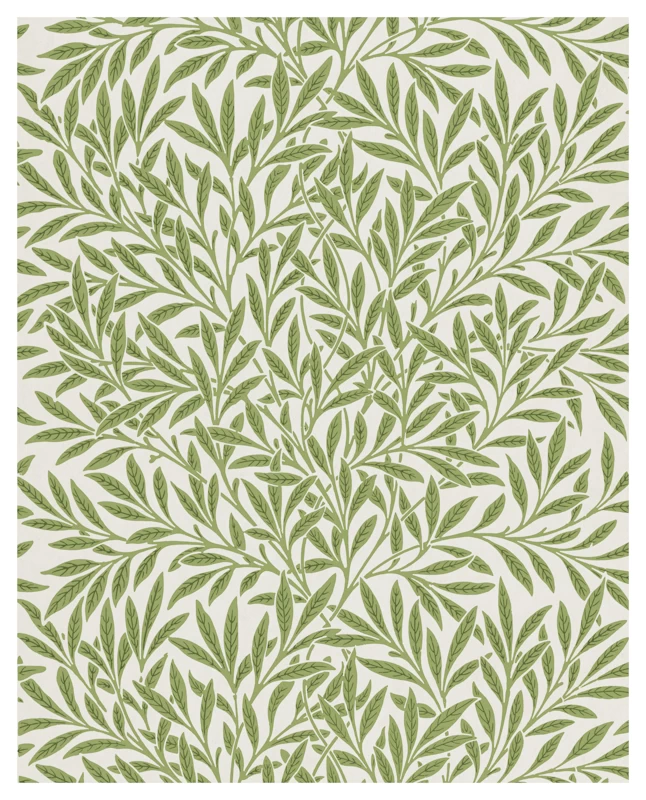

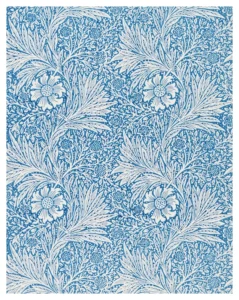

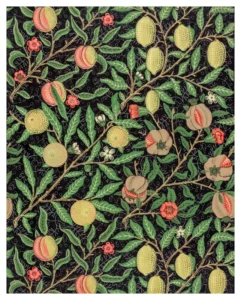

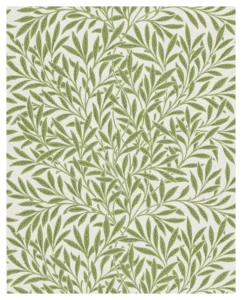

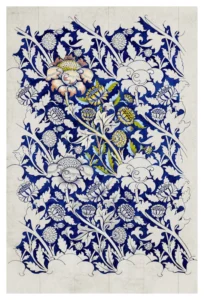

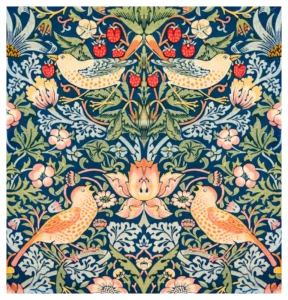

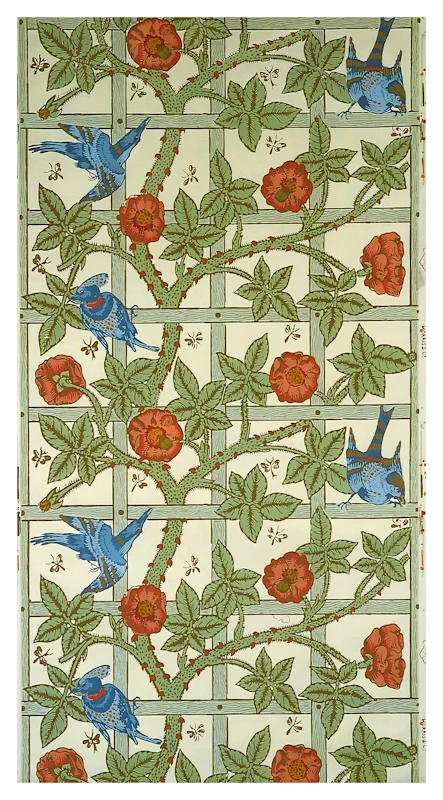

Morris’s designs often featured plants and animals that were common in the English countryside, like roses, ivy, and birds. By bringing these elements into people’s homes through his wallpapers and fabrics, he hoped to keep a connection to nature alive, even in the middle of cities. In patterns like Strawberry Thief, which shows birds stealing strawberries, or Willow Bough, which captures the soft curves of willow branches, Morris captured the vitality and peace of nature. These patterns offered an escape from the grime and grayness of industrial England.

His choice of colors also reflected his love of nature. Morris favored earthy tones like deep greens, blues, and warm reds, which he achieved by using natural dyes. Synthetic dyes were cheaper and easier to use, but they lacked the rich, warm quality of natural colors. Morris believed that only natural dyes could capture the true beauty of the plants and flowers he was depicting. His commitment to natural materials wasn’t just about quality—it was part of his larger respect for the environment and his rejection of the artificiality brought on by industrial production.

The Medieval Inspiration Behind His Patterns

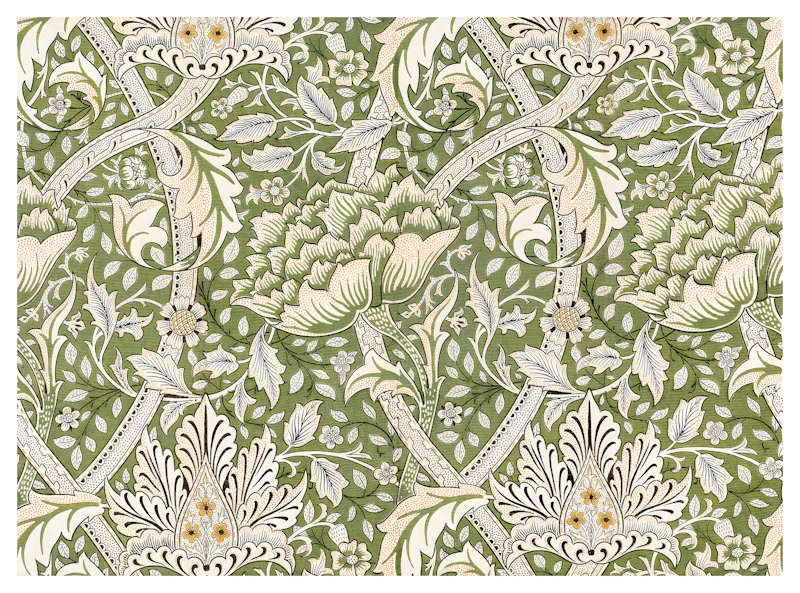

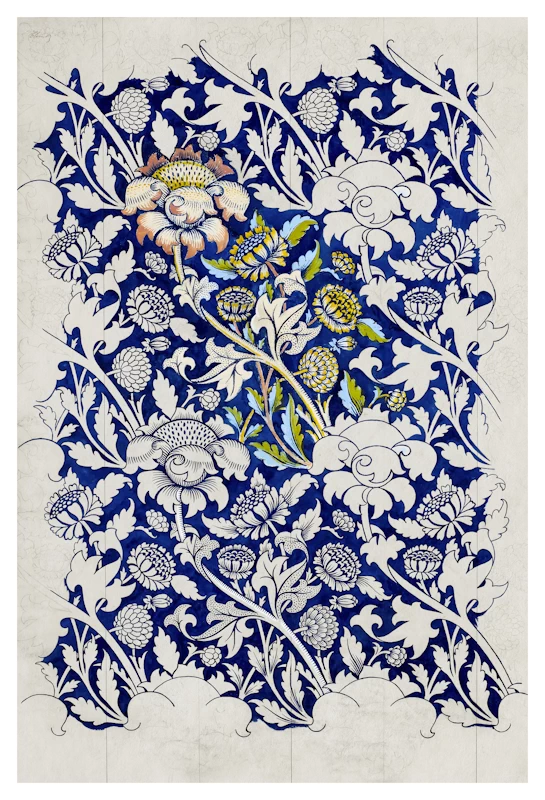

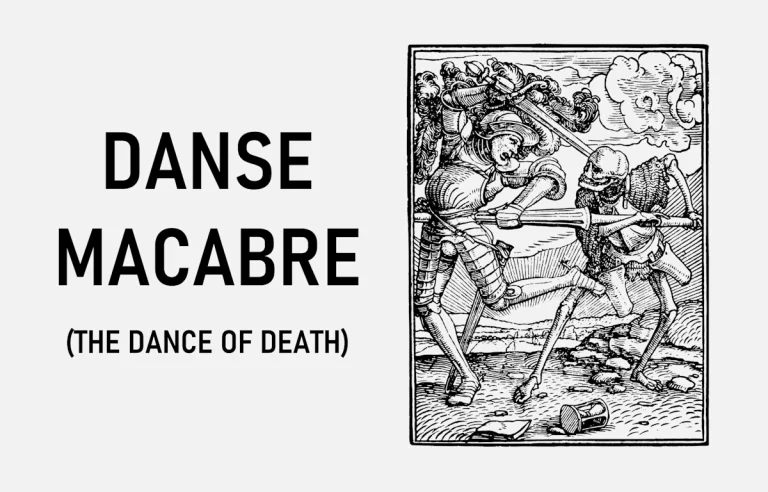

William Morris adored the Middle Ages, a time when he felt that art and work were united. In medieval society, skilled craftsmen belonged to guilds, working together to create everything from stained glass to furniture. Each piece was made with pride, care, and skill. To Morris, the medieval approach to craftsmanship represented a high point in human creativity, and he believed that society had lost this spirit in its rush toward industrialization.

Morris used bold, curling leaves inspired by medieval manuscripts and tapestries, as in Trellis. These designs weren’t just inspired by the shapes and styles of medieval art; they were meant to recall a time when art and craft were deeply respected. Morris wanted his work to feel like it came from a world where people took pride in what they made, where beauty mattered as much as function.

By drawing on medieval styles, Morris made his patterns a form of protest against the soulless products churned out by factories. His work was rich with detail, layered, and thoughtful, just like the tapestries and manuscripts he admired. This was his way of saying that art should be made by hand, with care and respect for the materials.

Beauty for Everyone: Art as a Political Mission

Morris had a radical belief for his time: he thought everyone, no matter how rich or poor, deserved to live surrounded by beauty. Victorian society was filled with a divide between the wealthy and the working class. While the rich could afford beautiful, handcrafted items, the poor were stuck with cheap, poorly made goods. Morris believed that this inequality was unfair and harmful.

He dreamed of a world where beautiful things were available to everyone, not just a privileged few. To him, art wasn’t just for galleries or wealthy homes; it should be in every home, filling everyday life with beauty. By creating wallpapers and fabrics that were accessible to a broader range of people, he aimed to make art a democratic experience, something that could enrich the lives of all people.

This idea was part of Morris’s larger political vision. He was a socialist who believed in the rights of workers and the importance of a fair, just society. He saw his patterns as part of this mission. Each wallpaper or fabric was a small step toward creating a world where people valued quality, fairness, and beauty over speed, profit, and exploitation.

Morris’s Legacy: Patterns with a Purpose

Today, William Morris’s patterns are still beloved, admired not only for their beauty but also for the philosophy they represent. His designs remind us that art is powerful, that it can stand against injustice and make our lives better. Through his commitment to craftsmanship, his respect for nature, and his belief in art’s power to create change, Morris left a lasting legacy.