Pseudoscience in the 19th Century

The 19th century was a remarkable era for scientific discovery, with groundbreaking advancements in fields such as biology, physics, and medicine. Alongside these legitimate developments, however, grew a fascination with pseudo-scientific ideas—concepts that mimicked science but lacked evidence.

Driven by curiosity, ambition, and sometimes outright deception, pseudo-science captivated both the public and intellectuals. Among its most notable examples were the Pasilalinic-Sympathetic Compass, phrenology, mesmerism, and the magneto-electric machine. These inventions and theories captured people’s imagination but also led to misunderstandings and even caused harm.

The Snail Telegraph

In 1850, French spiritualists Jacques-Toussaint Benoît and Abbé Jean-Baptiste Alexis Boiscommun claimed to have invented a device that could transmit messages over vast distances. Named the Pasilalinic-Sympathetic Compass, this invention relied on the idea of “sympathetic vibrations” between snails.

The inventors argued that once snails had come into contact, they maintained a mystical connection regardless of distance. The compass consisted of two paired devices, each holding snails arranged on dials marked with the alphabet. When a letter was chosen on one device, the paired snail on the other would supposedly respond, relaying the message instantaneously.

Though bold in concept, the device lacked any scientific basis. The inventors provided no evidence to support their claims, and the scientific community dismissed the compass as fanciful nonsense. However, the invention reflects the 19th century’s fascination with the unseen forces of nature and its aspiration to revolutionize communication, a goal that would eventually be realized through genuine technologies like the telegraph and telephone.

Phrenology

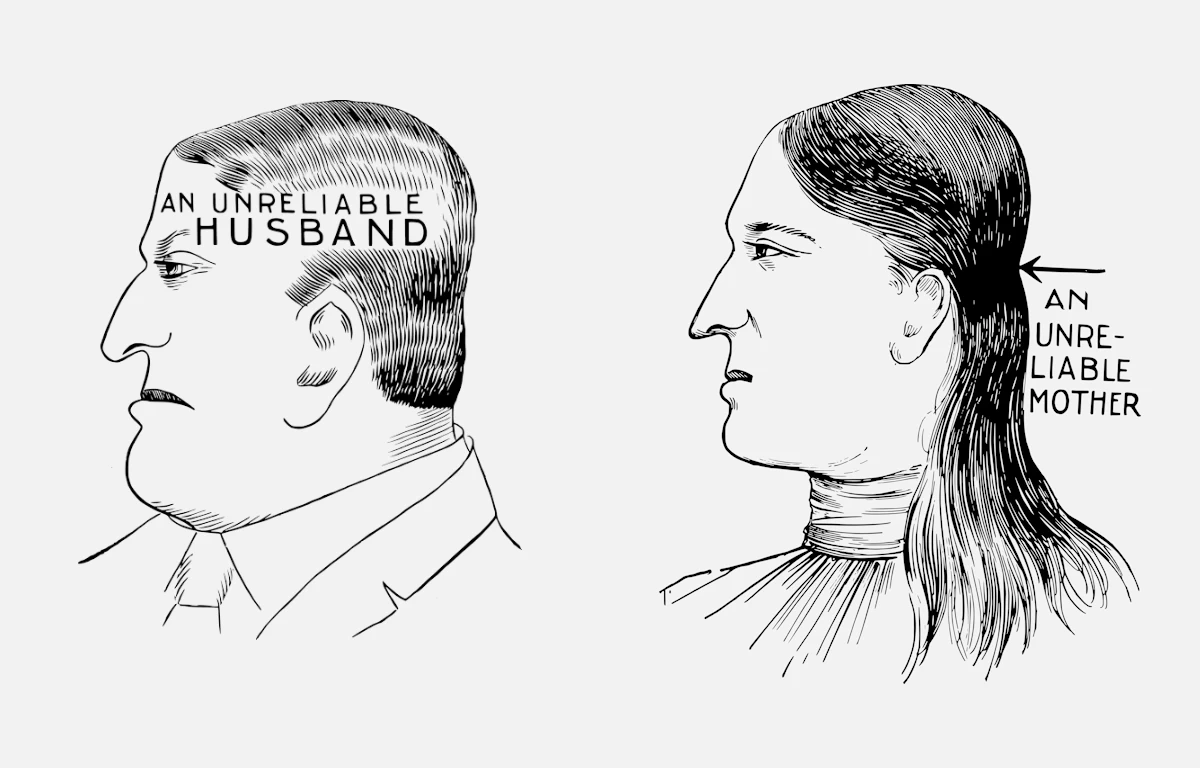

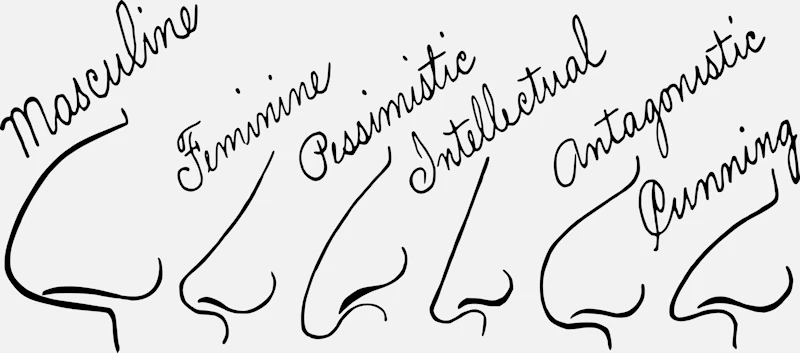

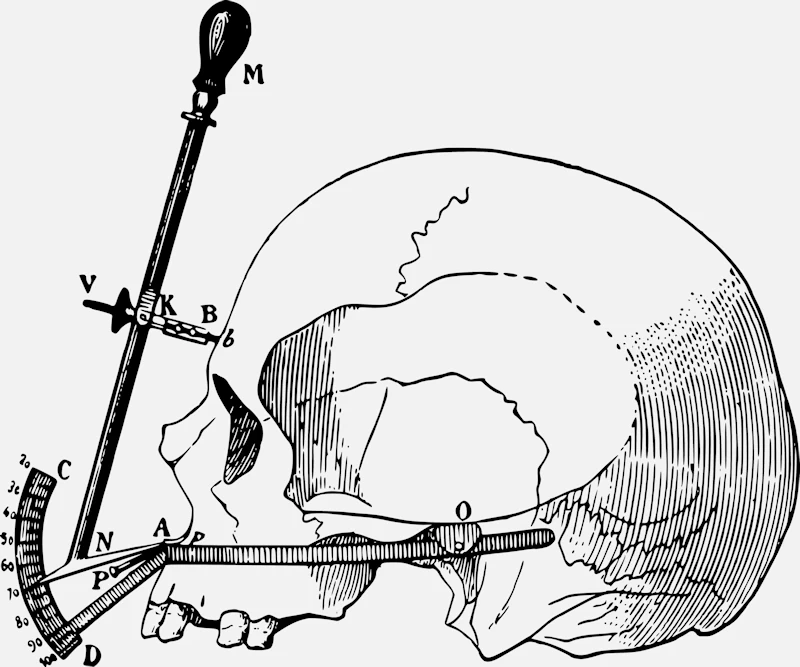

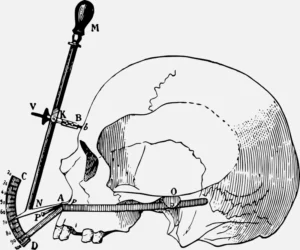

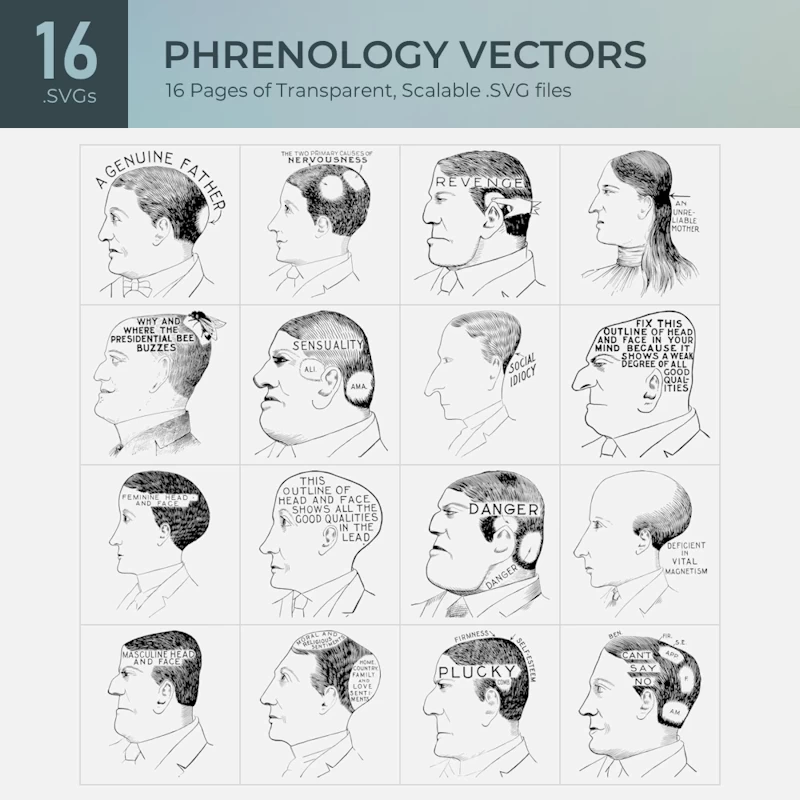

Phrenology was a popular but flawed idea in the 19th century. It claimed that a person’s character traits, intelligence, and behavior could be understood by studying the size, shape and proportions of their skull. Developed by Franz Joseph Gall and spread by followers like Johann Spurzheim, it became a widespread belief, even though it wasn’t based on real science.

Phrenologists believed the brain was divided into different parts, each controlling traits like kindness, creativity, or aggression. By feeling bumps and dips on a person’s head, they claimed they could figure out what someone was like or even predict their future success. This idea attracted many people who were eager to understand themselves and others better.

Unfortunately, phrenology wasn’t just used for self-discovery. It became a tool for discrimination. Phrenologists often measured skulls of people from different racial and ethnic groups and concluded—without valid evidence—that some groups were inherently superior to others. Women were also targeted by phrenology. It was often used to argue that women were less logical or capable than men. Phrenologists said this was because their skulls were smaller or shaped differently, arguments that made it easier for society to deny women equal rights and opportunities and were used to limit women’s roles in education, employment, and politics.

The so-called “scientific” results of phrenology were used to justify sexism, racism, colonialism, and the idea that some people were naturally superior. While phrenology has long been debunked, its harmful ideas about race and gender have left a lasting impact. In our world of ‘soyjak’ and ‘chad’ meme characters, it serves as a cautionary example of how pseudo-science can perpetuate stereotypes and inequalities.

Mesmerism

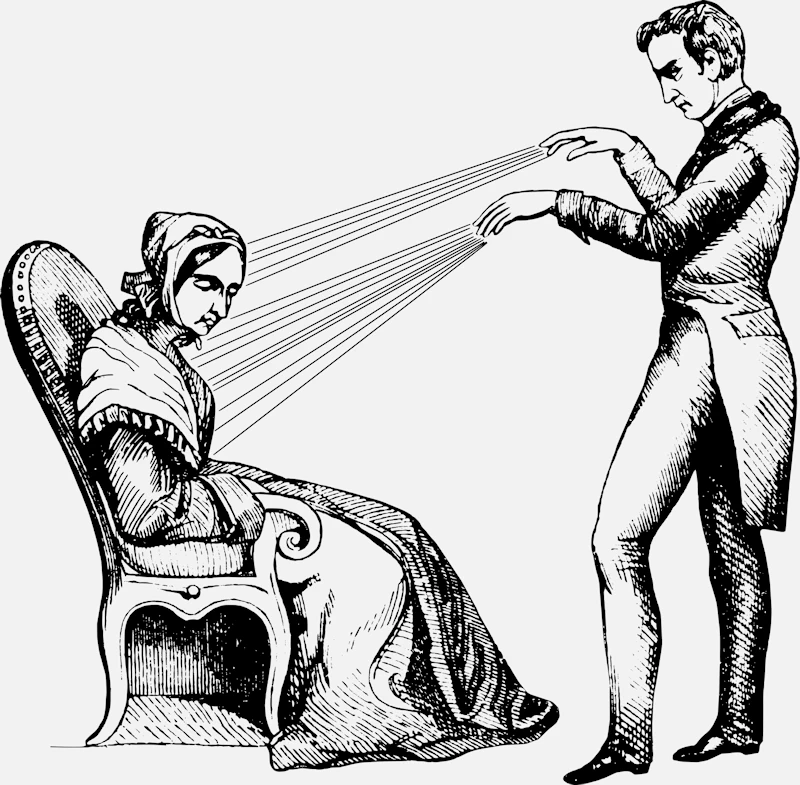

Another prominent pseudo-science of the 19th century was mesmerism, named after Franz Anton Mesmer, an 18th-century physician who proposed the existence of “animal magnetism.” Mesmer believed that an invisible magnetic fluid flowed through all living beings and that imbalances in this fluid caused illness. By manipulating this fluid through gestures or the use of magnets, he claimed to restore health.

Though Mesmer himself was discredited by a scientific panel in 1784, the idea didn’t disappear. In the 19th century, mesmerism made a comeback and practitioners expanded on Mesmer’s claims, suggesting that the technique could induce trance-like states or heightened awareness. These phenomena fascinated the public and even caught the attention of early psychologists.

One of the most famous proponents of mesmerism in the 19th century was James Braid, a Scottish surgeon who rejected Mesmer’s mystical explanations but acknowledged the observable effects of hypnosis—a term he coined. This shift laid the groundwork for the modern study of hypnotherapy. Despite this positive legacy, mesmerism was also associated with fraudulent performances staging dramatic demonstrations of “magnetic” healing or control. These spectacles often blended science with theater, drawing both ridicule and wonder.

The Magneto-Electric Machine

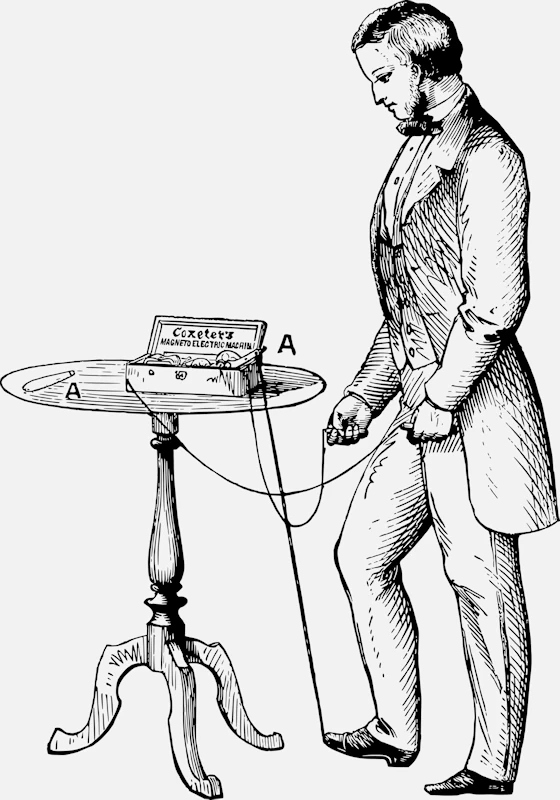

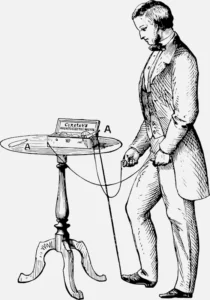

Electricity was one of the most exciting discoveries of the 19th century, and its potential seemed limitless. This enthusiasm gave rise to devices like the magneto-electric machine, which claimed to cure a wide range of ailments through electrical stimulation.

The machine worked by delivering small electric shocks to the body, often through handheld electrodes. Advertisements promoted it as a treatment for everything from chronic pain to depression. While the sensation of the electric current may have provided temporary relief for some symptoms, the machine was far from the miracle cure its promoters claimed.

Despite its exaggerated promises, the magneto-electric machine reflects an important transitional moment in medicine. It hinted at the therapeutic potential of electricity, paving the way for modern techniques such as electrotherapy. However, its popularity also underscores how pseudo-science often exploited public fascination with new technologies for profit.

Why Did Pseudo-Science Thrive?

In the 19th century, science was advancing rapidly, and people were eager to learn more about the world. Breakthroughs in fields like electricity, biology, and chemistry blurred the line between what was possible and what was speculative. For many, pseudo-science offered exciting explanations for the mysteries of nature or promised easy solutions to complex problems. The 19th century was also an age of spiritual revival, with movements like Spiritualism gaining popularity. These movements often intersected with pseudo-scientific ideas, blending curiosity with supernatural speculation.

Public fascination with pseudo-science was also fueled by a lack of rigorous scientific standards. The scientific method was still developing, and the peer review process was not as rigorous as it is today which made it easy for ideas that appeared scientific to gain widespread acceptance. Additionally, pseudo-science was often presented in accessible, entertaining formats, such as public demonstrations, pamphlets, or newspaper articles, making it appealing to a broad audience.

Pseudo-science from the 19th century may seem strange or silly today, but it had a lasting impact. Some ideas, like mesmerism, inspired real scientific discoveries. Others, like phrenology, caused harm by promoting stereotypes and justifying discrimination. These examples remind us why it’s important to question ideas and look for real evidence.