Tulip Mania: The World’s First Financial Bubble

Imagine a world where a single flower bulb could cost more than your house, your annual salary, or maybe even your life savings. Sounds absurd, right? Welcome to the Dutch Republic in the 1630s, where Tulip Mania—a whirlwind of flower-fueled financial madness—swept the nation into a speculative frenzy. It was the 17th-century equivalent of meme stocks or cryptocurrency, with people frantically investing in tulip bulbs.

Often called the first recorded financial bubble, Tulip Mania is a cautionary tale about greed, market speculation and the human tendency to chase trends. It’s also a fascinating chapter in history, full of rare blooms, wild price swings, and lessons we can still learn today.

The Flower That Launched a Thousand Trades

Tulips weren’t always a Dutch obsession. Originally from Central Asia, tulips traveled to Europe in the late 16th century, courtesy of traders from the Ottoman Empire. The flower’s vibrant colors and unique patterns immediately caught the eye of Europe’s elite, and before long, they became the must-have luxury item of the Dutch Golden Age.

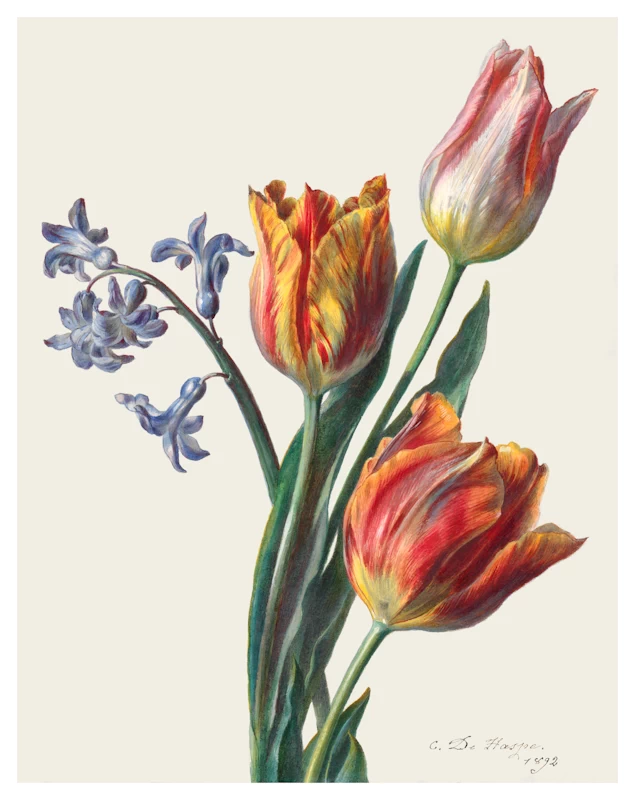

Now, these weren’t your average backyard tulips. The most prized ones were known as “broken” tulips, characterized by feathered streaks of contrasting colors or flame-like patterns on the petals. These unusual markings weren’t the result of intentional breeding but were caused by a virus known as the Tulip Breaking Virus (TBV). The virus infected the tulip bulb and disrupted the plant’s pigmentation, creating the vibrant and unpredictable patterns that captivated 17th-century collectors. While the virus produced these visually stunning effects, it also weakened the bulbs, making them less robust and harder to cultivate. This fragility added to their mystique and rarity, as the “broken” tulips were not only difficult to grow but also less likely to survive over time. The unpredictable nature of the virus meant that not every tulip would break in the same way, adding an element of chance and exclusivity to their appearance. What began as a biological abnormality became the ultimate status symbol during the tulip mania frenzy.

By the early 1600s, tulips were so prized in the Dutch Republic that they became a status symbol. But then, something peculiar happened: people stopped buying tulips to plant and enjoy them, and started buying them to make money.

The Tulip Trade: From Gardening to Gambling

What began as a flower market quickly turned into a speculative free-for-all. By the 1630s, tulips weren’t just flowers—they were investments. Wealthy merchants, middle-class artisans, and even farmers joined the frenzy, buying and selling tulip bulbs with the hope of turning a quick profit.

The prices of tulips skyrocketed, especially for rare varieties like the Semper Augustus, which was so valuable that one bulb could reportedly buy a mansion in Amsterdam. Here’s where it gets even wilder: people started trading tulips they didn’t even have yet. Through futures contracts, buyers and sellers agreed on prices for bulbs that were still in the ground. These contracts changed hands multiple times before the bulbs even bloomed. In a way, it was like flipping real estate, but with flowers. And much like today’s speculative bubbles, everyone thought they’d get rich. Why wouldn’t they? Prices were going up, and the only direction seemed to be higher.

Peak Madness: The Highs of Tulip Mania

At the height of Tulip Mania in 1636–1637, the tulip market was blooming (sorry, booming). Trading often took place in taverns, where ordinary citizens rubbed shoulders with wealthy merchants, swapping tulip contracts over drinks.

A few documented examples give us a glimpse into the insanity:

- A single bulb of Semper Augustus sold for as much as 10,000 guilders, roughly the cost of a luxury townhouse at the time.

- An artisan reportedly traded everything he owned—including his house and business—for a few tulip bulbs.

- Bulbs that weren’t even particularly rare were selling for absurd sums. Imagine paying $100,000 for a mid-tier handbag—you get the idea.

It wasn’t just about greed; it was also about FOMO (fear of missing out). People saw their neighbors making fortunes in the tulip trade and didn’t want to be left behind. Unfortunately, as with all bubbles, what goes up must come down.

The Bubble Bursts

In February 1637, the tulip market collapsed faster than you could say “Semper Augustus.” The reasons aren’t entirely clear, but it seems buyers simply stopped showing up at auctions. Perhaps prices had reached a point where no one was willing—or able—to pay. As confidence evaporated, panic set in. Sellers rushed to offload their tulips, flooding the market and causing prices to plummet. Bulbs that had been worth a fortune days earlier were suddenly worth next to nothing. Many people who had gambled on tulips—often by selling their belongings or taking on debt—were left financially ruined. The Dutch government tried to step in, offering to cancel tulip contracts for a small fee, but it was too late to stop the damage. The tulip bubble had burst, leaving behind a trail of economic and emotional devastation.

Lessons from Tulip Mania

Tulip Mania has become synonymous with financial folly. It’s referenced in economics textbooks, pop culture, and everyday conversations about market hype. Whenever someone says, “This is the next Tulip Mania,” you know they’re talking about something overhyped and likely doomed to crash.

As a cautionary tale, it serves as a reminder of the risks of speculative bubbles. Whether the investment is in flowers or cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, the lesson remains the same: avoid letting FOMO cloud your judgment, and always take the time to thoroughly understand the market before diving in.

Tulip Mania also underscores the importance of recognizing intrinsic value. Tulips, for all their beauty, were never worth the fortunes they commanded during the mania. When people lose sight of actual value in favor of speculative frenzy, markets become dangerously vulnerable to dramatic crashes.

Finally, the phenomenon reveals a truth about human behavior that transcends time. Greed and the temptation of quick riches are constants that fueled Tulip Mania and continue to drive speculative bubbles today. Even 400 years later, these traits remain ingrained in the way some people approach markets—proof that history has a tendency to repeat itself.